RESEARCH EXCELLENCE INITIATIVE

FREEDOM OF RESEARCH – SCIENCE FOR THE FUTURE

‘Freedom of Research – Science for the Future’ series consists of articles, interviews and short videos presenting research conducted by the winners of the ‘Freedom of Research’ call for proposals

dr Mariola Paruzel-Czachura, prof. UŚ

Who are you going to save: a dog, a human, or a chimpanzee?

| Olimpia Orządała |

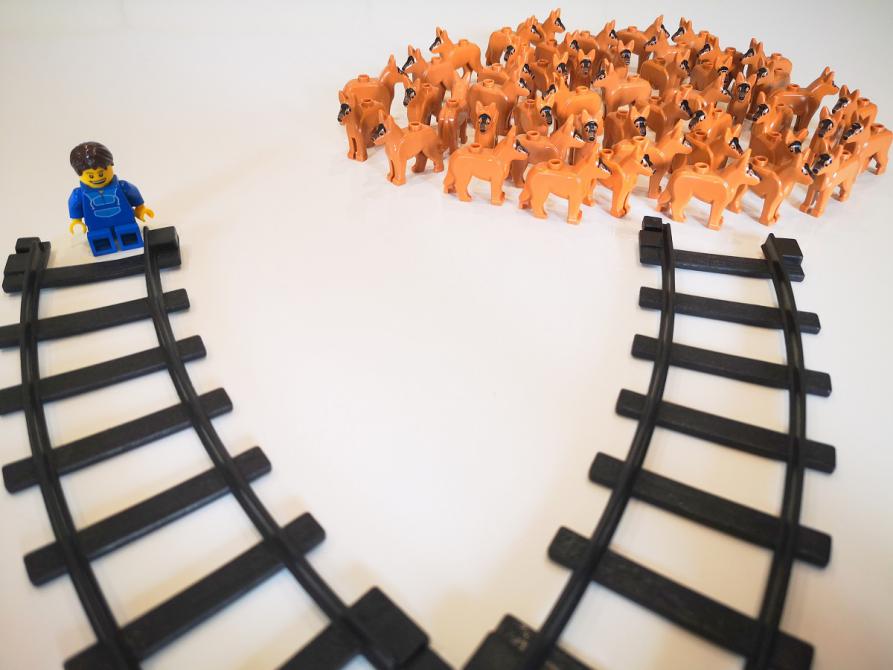

The trolley problem is one of the most famous thought experiments in the world. The out-of-control trolley goes flying down the tracks and is going to run over five people who are tied down to the tracks and cannot move. You have the option to pull the lever and divert the trolley onto a second track with only one person on it. This experiment was developed by Philippa Foot in the 1960s and comes down to a question about whether you can sacrifice one person to save five. But what if we modify a little the basic version of this moral dilemma and put a human and an animal on the tracks? Who will be saved more often by adults, and who by children?

Mariola Paruzel-Czachura, PhD, Associate Professor from the Institute of Psychology of the University of Silesia | photo by Julia Agnieszka Szymala

To replicate American research

The first to attempt to answer this question were American scientists in an article published in Psychological Science. Mariola Paruzel-Czachura, PhD, Associate Professor from the Institute of Psychology of the University of Silesia, co-author of the article Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin financed by from the first edition of Freedom of Research under the Research Excellence Initiative, replicated their research. The idea to recreate the study came to the USil scientist after reading the article and after the Silesian Science Festival KATOWICE when she borrowed her sons’ LEGO set to make her stand more attractive and to explain to children what the trolley problem is about a little easier. A psychology student, and co-author of the article, that was helping out with the festival stand noticed that children tend to save a LEGO dog more often than a LEGO human. Shortly after the festival, Mariola Paruzel-Czachura, PhD, Associate Professor read the above-mentioned article.

Those American scientists used graphical materials depicting humans, dogs, and pigs and research subjects made their decision on who to save using a tablet. As it turned out, children were saving animals more often than adults. It is a revolution, to some degree, because it contradicts the theory that people are born with a preference for their own species. ‘American scientists proved that preference for species is weaker in children than in adults. They also encouraged more research into the topic. I decided to check whether Polish children make similar choices’, says M. Paruzel-Czachura.

The psychologist had some reservations regarding the procedure developed by Americans, specifically the use of simple, black-and-white icons depicting the characters. Doubts concerned whether children will associate such a character with a human. The scientist contacted the authors of the study and shared her idea. Thus, a joint study with a new procedure was established to test the hypothesis in another culture.

LEGO bricks

The scientist from the University of Silesia together with the team conducted research on 412 people, including 212 children 9 years of age and younger and 178 adults. The experiment used LEGO bricks assembled to represent different scenarios. Children participated while in preschools and schools and adults filled in online questionnaires.

‘Children must have a graphical representation of the thing because it makes it way easier for them to come to a decision’, says the USil psychologist.

The research preparations alone took over a year. Selecting the LEGO bricks and creating a proper procedure were the most time-consuming tasks.

‘Somebody who is not a scientist might think that we simply bought some LEGOs and did the study’, says the researcher. ‘Meanwhile, before we did anything, we spent lots of time thinking about which animal to select. When we reached a decision, we analysed each figurine, e.g. as to whether the people smiled or not. When it comes to the dog, we analysed over 50 figurines. Chimpanzees were ordered from Hong Kong and the delivery took a couple of months.

After the method was selected and the procedure was developed, we moved on to pre-registering the study to avoid any unethical behaviour in science. Next, the USil psychologist and her American colleagues conducted statistical analyses and wrote the article, which was published in a prestigious journal.

A novelty in the approach to replicating research, aside from using LEGO bricks, was also testing two preference options. Children and adults not only made the decision of who to save but also who to give a snack to: a human, a dog, or a chimpanzee.

‘I did not believe that the result would be the same’, admits the scientist. ‘Even though the assumption was that we are replicating the study and checking whether it will yield the same results, I thought that Polish children wouldn’t choose to save animals. But I was proven wrong already at the testing stage.

LEGO bricks used during the study | photo by Mariola Paruzel-Czachura, PhD, Associate Professor

Anthropomorphism of animals

Both Polish and American children were choosing to save the animals more often than adults. Why is that? We still don’t know. One hypothesis is the so-called anthropomorphism.

‘Currently, we are testing the hypothesis that in WEIRD countries (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich and Democratic) children often encounter animals that are anthropomorphised. They watch e.g. Paw Patrol, The Penguins of Madagascar, and other cartoons’, explains the psychologist.

Interestingly, children preferred dogs over chimpanzees – they saved them and gave them snacks more often. It might have something to do with the mentioned anthropomorphism and common contact with dogs.

‘We need to remember that our hypothesis stated the opposite. According to the theory, we should prefer the human species and those close to it. We assumed that children would select those animals that are higher in the animal hierarchy. It did not turn out that way, so the anthropomorphism seems sensible – admits M. Paruzel-Czchura, Associate Professor.

The researcher also checked if having a pet and visiting a zoo had an impact on the decision made. As it turns out, it is irrelevant. Similarly, the gender of the study subjects does not seem to matter. However, adults were more often indecisive than children.

‘In my opinion, children see the world in a simpler way and thanks to that it is easier for them to make a decision. Either left or right. Meanwhile, adults think things over and search for a hidden truth’, says the researcher.

Crisis in psychology

Some time ago, a replication crisis in psychology was announced. M. Paruzel-Czachura thinks that this is the best thing we could have hoped for. In the past, studies were conducted on small or very specific sample groups and their results were extrapolated to encapsulate all humans. An example can be the experiment carried out by Alber Bandury with the Bobo doll, which aimed to prove that children exposed to aggressive behaviour become more aggressive themselves. The study sample was made up of Stanford University lecturers’ children.

‘Hearing this, each reasonable person would come to a conclusion that it is absurd to draw conclusions about all people on the basis of a single study with a specific research group’, says the scientist.

The psychologist argues for the need to conduct the same studies also in other countries. The development of statistics and methodologies allowed us also to understand that we need to test larger sample groups so as not to skew the results. Prior, studies were conducted on e.g. 50-100 people, while now we need thousands. There are special programmes to calculate how many people should be included in the sample groups.

‘Psychology reached such a sophistication level that without a little bit of programming you can’t really carry out any studies or analyses’, points out M. Paruzel-Czachura. ‘I learned programming and counting in R [R Project for Statistical Computing] when I got accepted to a post-doc fellowship in the United States.

Currently, to publish an article in the field of psychology, you need to reach high quality levels on each of the steps: research design, pre-registration, and statistical analysis. This is why psychology became more of a team field of study – one researcher is simply not able to conduct a good study. Research tends to also be very competitive, time-consuming, and underfunded, which is a problem.

‘Psychology is becoming an increasingly difficult field. In comparison with other countries, we have very limited resources. For example, my friends from Ireland (without an additional grant) do not have any problems in attending a conference two or three times a year, with each costing around PLN 10,000’, admits the researcher and adds: ‘I get involved in many international projects out of sheer passion. As a result, I have written papers with over 300 people. I think that this is the most important part of my work. I am certain that when looking back on my life, the thing that I will be most proud of will be these projects in which I was one of the 300 authors because it is a bottom-up initiative to check whether each given thing works the same in 300 countries. This work is meaningful’, sums up the researcher from the University of Silesia.

The article entitled ‘Who are you going to save: a dog, a human, or a chimpanzee?’ was published in the April issue of Gazeta Uniwersytecka UŚ (USil Magazine) no. 7 (317).