RESEARCH EXCELLENCE INITIATIVE

FREEDOM OF RESEARCH – SCIENCE FOR THE FUTURE

“Freedom of Research – Science for the Future” series consists of articles, interviews and short videos presenting research conducted by the winners of the “Freedom of Research” call for proposals

Marta Baron-Milian, PhD

The mysterious beginnings of the Polish avant-garde

| Olimpia Orządała |

Anatol Stern, Aleksander Wat or Bruno Jasieński are names that we associate with Polish futurism. However, none of them was the one who initiated it. This role is played by a writer who is now somewhat forgotten and usually marginalised in the historical and literary narrative – Jerzy Jankowski from Vilnius.

Marta Baron-Milian, PhD from the Institute of Literary Studies of the University of Silesia in Katowice, winner of the first edition of the “Freedom of research” competition as part of the Research Excellence Initiative, decided to show the role of Jankowski in the first years of Polish futurism. The works carried out by the literary scholar are part of the research devoted to the beginnings of the Polish avant-garde.

“The subject of my research project focused on the traces of the first avant-garde practices in Polish literature. I mainly dealt with futurism, the history of which is a narrow part of the history of the Polish avant-garde, falling in the years 1918–1924. However, I was particularly interested in an even shorter period – the years 1918–1921, which is actually the very beginning of the futuristic movement”, explains the researcher.

The history of Polish futurism focuses on two groups: one in Warsaw and one in Cracow, which merged in 1921 and have been working together ever since. Although the historical and literary narrative of Polish futurism has never been coherent, due to the significant differences between individual poetics, it emphasised their common features, characteristic of the futuristic avant-garde, inspired by Italian and Russian patterns.

“During previous research, it caught my attention that before the merger of the two groups, between 1918 and 1921, the joint avant-garde practices of Aleksander Wat and Anatol Stern were significantly different from those which emerged later and differed from what we mean by futurism, dadaism or surrealism, avoiding thinking in terms of directions or movements at all. Undoubtedly, they had an avant-garde character, were inspired by topics that were of interest for the Western and Eastern avant-gardists, but processed them in a completely different way”, explains M. Baron-Milian, PhD.

Stern and Wat called themselves neo-futurists and primitivists, forming the Warsaw group. According to the researcher, however, they were linked in a special way by their Jewish origin, “being foreign in language”, which can be clearly seen in their earliest works, especially in their joint appearances.

“The neo-futurists positioned themselves in relation to their Jewish origin in various ways”, states the literary scholar. “On the one hand, they masked their identity, and on the other hand, they did the opposite – in various ways they ‘played’ in parodies and provocations, giving, for example, anti-Semitic lectures. It seems that these matters are well known, but in fact, the beginnings of the Polish avant-garde are rarely interpreted in this very perspective – as a kind of a ‘minority’ practice.’”

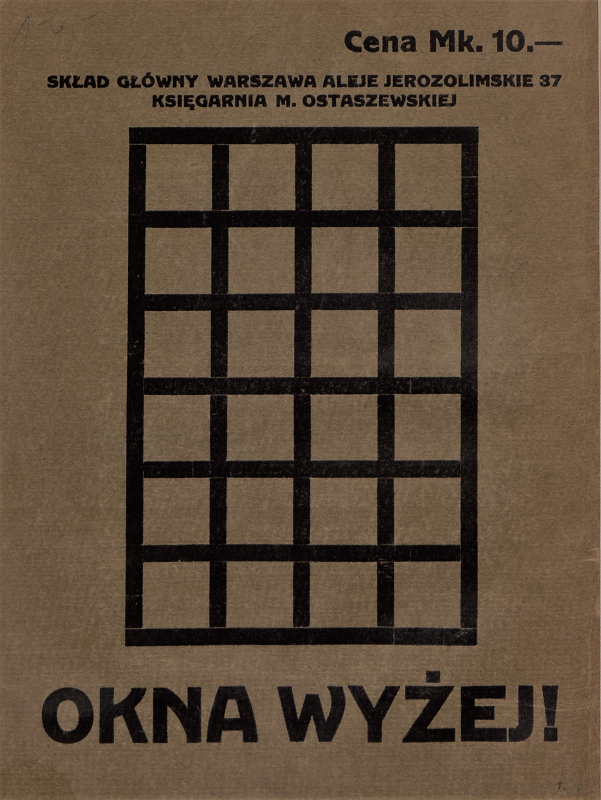

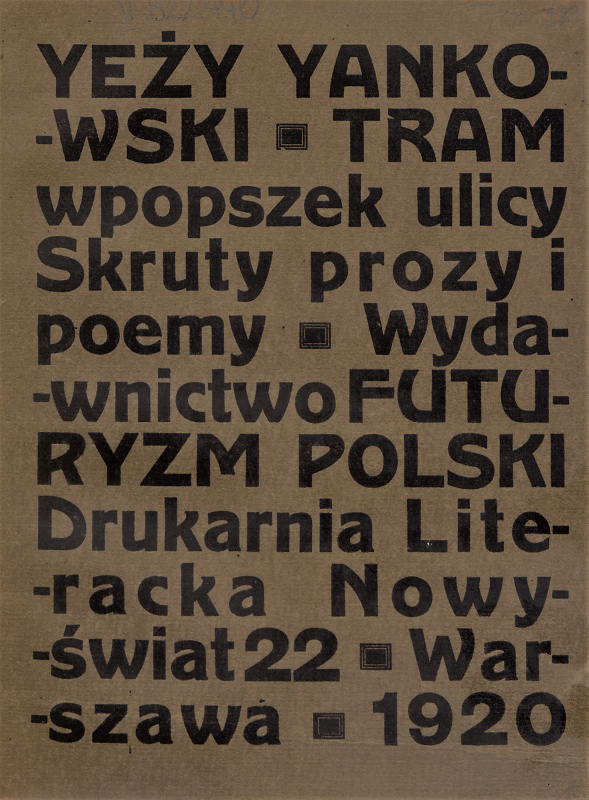

During her searches in the archives, Jerzy Jankowski, who seems to be a marginalised figure, despite being considered the first Polish futurist, especially attracted the attention of the competition winner. Although a number of articles have been written about the poet, there is only one book about him (by Paweł Majerski, PhD, Associate Professor from the Institute of Literary Studies of the University of Silesia). This marginalisation results from the fact that only one volume written by Jankowski is known today – “Tram wpopszek ulicy” (eng. “Tram across the street”), the rest of his texts are lost.

This work is the first Polish futuristic volume, consisting of poetry, prose and journalistic articles. It was post-dated to 1920, but in fact was already published in 1919, as evidenced by the reviews of October 1919. Interestingly, Jankowski’s journalistic output, unlike his poetry, is enormous. As a journalist, he travelled to many European cities and when he stayed somewhere longer, he published in the local press. M. Baron-Milian, PhD admits that it would be difficult to collect all journalistic publications written by the first Polish futurist because it would involve going through an enormous amount of material. However, during the research conducted as part of the project (mainly on press materials), it was possible to find several dozen scattered and more widely unknown poetic, prose and journalistic texts by Jankowski. They depict the writer’s extremely broad interests and show that foreign travels to, among others, London, Paris or Moscow, allowed Jankowski to get to know the avant-garde of various countries first-hand.

“Jankowski is a very interesting figure. He caught my attention with his extraordinary biography”, admits the literary scholar. “He is a tragic figure. After the release of ‘Tram wpopszek ulicy’, so when Polish futurism begins, his ‘artistic’ history actually ends. As a result of alcoholism and probably mental illness, the poet removes himself from public life, although it is not known whether he ceases his creative activity. He dies in a psychiatric hospital in Kojrany, murdered by the Nazis in 1941. We do not know much about the last twenty years of his life, but from various stories of friends it is known that in the hospital he continued to preach his “proclamations”, and maybe even manifestos…”

The fourth page of the cover of Jerzy Jankowski’s “Tram wpopszek ulicy” | source: National Library, public domain

The cover of Jerzy Jankowski’s “Tram wpopszek ulicy” | source: National Library, public domain

W As part of the competition “Freedom of research” M. Baron-Milian, PhD conducted research in the archives of the National Library in Warsaw and in libraries in Vilnius. In addition to journalistic texts, the researcher found Jankowski’s literary works, brochure publications, and the series “Czerwone pieśni” (“Red Songs”), which she managed to reconstruct on the basis of poems published in various newspapers. The texts found, apart from showing Jankowski’s biography and works in a broader perspective, also say a lot about the very activity of avant-gardists in Vilnius or poetry evenings organised by Polish futurists.

“I think that Jankowski’s role was much greater than it seems. The author of ‘Tram’ influenced, for example, Anatol Stern, one of the most important Polish futurists”, admits the literary scholar. “Stern mentions Jankowski in many artistic texts as an important figure, a bit mystical, shrouded in mystery, charismatic, but above all tragic.”

One of the valuable sources of knowledge about the role of Jankowski turned out to be the typescript of the poet’s sister’s memories. Her name was Janina Jankowska-Orynżyna and M. Baron-Milian, PhD found the text written by her at the National Library in Warsaw. The stories contained in it show the history of Polish futurism in a different light and depict Jankowski as an animator of the avant-garde, a great speaker delivering the first futuristic manifestos.

The poet was the organiser of the famous futuristic evenings in Vilnius, which were often held surrounded by an aura of scandal. The researcher followed reports from press meetings of that period.

M. Baron-Milian, PhD was also the laureate of the second edition of the competition “Freedom of research”, under which she will continue research on the history of avant-garde and futurism.

“While conducting research on the experimental artistic practices of representatives of the Polish avant-garde in the context of the theory of ‘smaller literature’, this time, using part of the funding received in the competition, I would like to go to Archiv der Avantgarden of Egidio Marzona in Dresden, where the first Polish futuristic print was discovered a few years ago – the leaflet TAK (eng. YES), by Stern and Wat, and to Berlin. These are obligatory places to visit for avant-garde researchers”, admits the literary scholar.