The approx. 8 m high opening of the Lower Castle Cavern, built-up with a wall, state before the start of excavations | Photo by Andrzej Tyc

| Maria Sztuka |

The Kraków-Częstochowa Upland is a real treat not only for the lovers of landscapes straight from the Jurassic period. It is also a huge testing ground for scientists. Two thousand caves attract archaeologists, crustal researchers, anthropologists and specialists in all natural sciences. According to speleologists, caves are a great repository of data about the past.

In 2018, scientists conquered the Lower Castle Cavern in the Jurassic Olsztyn. The resourceful owners of the castle, i.e. Fundacja Wspólnoty Gruntowej Wsi Olsztyn [Foundation of the Land Community of the Olsztyn Village], obtained large EU funds (from the Regional Operational Programme of the Silesian Voivodeship) for the implementation of the project ‘Increasing the attractiveness of the Olsztyn Castle by performing the necessary conservation and restoration works’. The people of Olsztyn have been joined by the Przyroda i Człowiek Foundation [Nature and Human Foundation], the founders and members of which are graduates of the Faculty of Natural Sciences of the University of Silesia. However, before the renovation works began, the hill, and above all the cave, was made available to scientists. Specialists from the following universities participate in interdisciplinary excavations: Jagiellonian University, University of Wrocław, University of Silesia, as well as specialists from Polish Academy of Sciences. The team’s work is coordinated by archaeologist Mikołaj Urbanowski, PhD.

Half a century ago

The first research in the Lower Castle Cavern was carried out in the years 1969–1970, and was led by Jerzy Kopacz and Andrzej Skalski, museum workers from Częstochowa. In the silt of the cave, they found, among others, a rich assemblage of bone remains including both Pliocene, Pleistocene and Holocene faunas, as well as tools from the Middle and Upper Palaeolithic. Over 300 artifacts found at that time were deposited in the Częstochowa Museum.

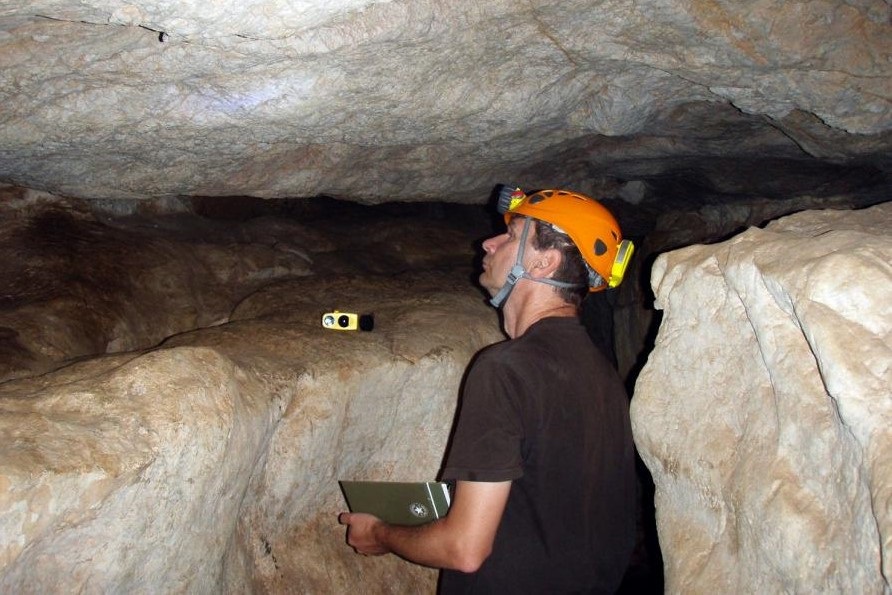

Andrzej Tyc, PhD, a geomorphologist and speleologist from the Institute of Earth Sciences of the University of Silesia, is part of the interdisciplinary team, which began research work in the Lower Castle Cavern 4 years ago. He has extensive experience in the field. He has participated in many scientific expeditions in various corners of the world, led, among others, works of an international team as part of the European-Australian research project HYPOCAVE, he currently participates in the implementation of research projects in the Colca Canyon in Peru and the Dinaric Alps in Slovenia. In the Kraków-Częstochowa Upland, he pursues his scientific passions in the study of Jurassic caves. He participated in the exploration of the Biśnik Cave in the Dolina Wodącej [Wodącej Valley] (near Smoleń), where traces of man from over 200,000 years ago were discovered, as well as the Jaskinia Głęboka [Deep Cave] in Podlesice. The scientist published the results of his research in, among others: ‘Geochronometria’, and recently in the ‘Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research’. The scientist speaks with appreciation of the results of research conducted 50 years ago in the Lower Castle Cavern.

“This collection is one of the most northerly inventories of the Mikocka culture (Middle Palaeolithic). At that time, the cave was probably a small hunting shelter used by Neanderthals. Unfortunately, at the end of the 1970s, the archaeological excavations were filled in, without being thoroughly explored, but the documentation prepared at that time made our work much easier” emphasises Andrzej Tyc, PhD.

Andrzej Tyc, PhD | Photo by Armstrong R. Osborne

Testing ground

The first to start work was a small excavator, which picked up heaps of garbage from the surface, and also removed rubble from Jerzy Kopacz’s excavations. The actual study of the sediments in the cave included large parts of the silt that had not been disturbed so far. The settlement selected by archaeological methods required special attention, after “cosmetic” treatments, i.e. careful rinsing on sieves, it was possible to isolate many Palaeolithic, medieval and modern artefacts, as well as bones of fossil fauna.

In 2019, scientists conducted geophysical research inside the cave using electrical resistance tomography and an 8-meter hole drilling. They showed the presence of fissures in the cave floor filled with sediments and rock rubble, as well as voids in its central part. Some corrections and verifications of the existing knowledge about the cave were made. For example, the level previously considered to be the bottom of the cave turned out to be a sediment in which remains of animals from millions of years ago were found – admits the geomorphologist. The results will soon be included in a scientific article that is being prepared.

“During research using geophysical methods conducted by a team from the University of Wrocław with the participation of archaeoseismologist Krzysztof Gaidzik, PhD from our Faculty, we made several profiles in the foreground of the cave. We came up with an idea that as a result of an earthquake, a fragment of the rock at the mouth of the cave was torn off and the tower was partially destroyed, as traces of its reconstruction are visible, which is also confirmed by historical records – says the researcher.

Unusual find

In the undisturbed silt, scientists made a surprising discovery: the remains of a metallurgical furnace from the 15th and early 16th centuries for copper smelting. The uniqueness of the find is evidenced by its location. The high temperature and a lot of toxic secretions during smelting made it a dangerous occupation, so hiding the furnace in a cave may indicate a desire to keep the activity conducted here secret.

“This is the only such finding in Europe. A detailed scientific article about it will be published soon, its main author is Michał Wojenka, PhD from the Jagiellonian University, who specialises in medieval and modern archaeology”, adds the speleologist.

Of course, the medieval smelting furnace is nothing like a modern device, because it is a cavity to which numerous channels lead. The thesis about the existence of the furnace is confirmed by the found fragments of clay blowers used to aerate the melt.

In the laboratory of the Institute of Earth Sciences of the University of Silesia, researchers conducted an experiment consisting in burning sediments taken from the vicinity of the furnace at high temperature (500-1000°C). Comparison of the colour, structure and mineral composition of the sediments transformed in this way, with those from the silt of the cave will provide additional evidence to prove the existence of a metallurgical facility in it.

Forge and pantry

There are no dripstones in the Lower Castle Cavern. The huge opening, at the threshold of which during the Pleistocene glaciation the front of the ice sheet was located, caused – explains the researcher – the cave to freeze, and therefore it does not have dripstones, which is characteristic of the majority of Jurassic caves. In the remaining ones, where dripstones could have survived, they were destroyed as a result of calcite exploitation, which was completed in the vicinity of Olsztyn in the first half of the 20th century.

For scientists, the most important elements found in the cave are the sediments, the morphology of the walls and ceiling, hollows and niches that were created millions of years ago, long before animals appeared here. The next mysteries that are being discovered are the traces of human activity at the end of the Pleistocene. The artifacts found in the cave date back to the Magdalenian period (late Palaeolithic). These are, among others, flint tools and reindeer bones.

“From the series of sediments with artifacts, we also took samples of sediments for optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) dating, which allows us to determine when the sun rays last fell on the sediments before they were covered with successive layers. Hence the precise dating of the finds: 13,000–14,000 years”, explains Andrzej Tyc, PhD.

For the Neanderthals, the cave was certainly a hunting shelter, as evidenced by numerous traces of flint tools, while from the 14th century onward, when Casimir the Great built a castle on the hill, the cave served as a forge, and later as a pantry near the castle.

The longest of the previously discovered caves of the Kraków-Częstochowa Upland is the Wierna Cave (Ostrężnik), the total length of its corridors is over 1 km. The Lower Castle Cavern is only 20 meters long, but it is its height that is impressive, reaching up to 12 meters in some places. According to the speleologist, it is one of the most valuable archaeological and paleontological cave sites in Poland. Despite centuries of anthropogenic transformations, research and robbery excavations, it has retained many important features – the original relief of the walls and ceiling, as well as fragmentarily preserved silt profiles, archaeological monuments and fossil fauna.

“We have to put the results of our analyses together like a puzzle, but we’re getting close to the finale”, assures the researcher. In the RPO project, scientific research was a secondary objective. The priority was to prepare the cave for tourist purposes and these works are nearing completion. So soon we will be able to admire not only the inside of the cave and the artifacts exhibited in it, but also the reconstruction of the mysterious smelting furnace.

Article “Secrets of the Lower Castle Cavern” was published in the December issue of University of Silesia Magazine No. 3 (303).