Salmons travel thousands of kilometres to reach their spawning grounds | Photo by Marcos Paulo Prado, Unsplash

Motherhood takes different forms in wildlife. Nonetheless, each of them requires a bigger or smaller sacrifice of a mother’s time, energy, health, and at times life. Although being an old evolutionary mechanism, it is hard to pinpoint the specific moment motherhood emerged.

‘It borders on impossible to pinpoint the specific moment in the history of our planet’s life when maternal care emerged,’ explains Prof. Karina Wieczorek from the USil Faculty of Natural Sciences. One of the oldest proofs of such care might be the remains of a family of hadrosaurs of the genus Maiasaura, a dinosaur living in the Cretaceous Period. ‘Its generic name might be literally translated as a good mother lizard. When unearthing their nests, scientists discovered the remains of eggshells and fossilised bones of young and adult dinosaurs. This alone might indicate a sort of parental care in these reptiles,’ adds the scientist.

Quality or quantity?

Thanks to biological evolution, we distinguish a wide array of parenting strategies among different species. However, generally, we can indicate two prominent reproductive strategies:

- r-strategy – the high quantity compensates for a high death rate. Mothers invest little effort in taking care of their offspring,

- k-strategy – a small number of offspring allows parents to commit to their protection and upbringing.

If we tried to interpret these behaviours from our human perspective, we would probably say that the r-strategy is implemented by bad moms, whereas the k-strategy is a trait of exemplary moms. Prof. Karina Wieczorek explicitly states not to succumb to stereotypes: ‘We should take into consideration the evolutionary success and effective strategies that have been used for thousands of years.

Female orangutans may nurse their young until they are eight | Photo by Dan Dennis, Unsplash

Various faces of motherhood

One of the most poignant yet disturbing manifestations of maternal care—where the mother sacrifices her own life—is matriphagy, the consumption of the mother by her offspring. It has been observed in the Mediterranean species of spider called Stegodyphus lineatus and the Japanese species of earwig called Anechura harmandi. Juveniles consume their mother when they are unable to find another food source.

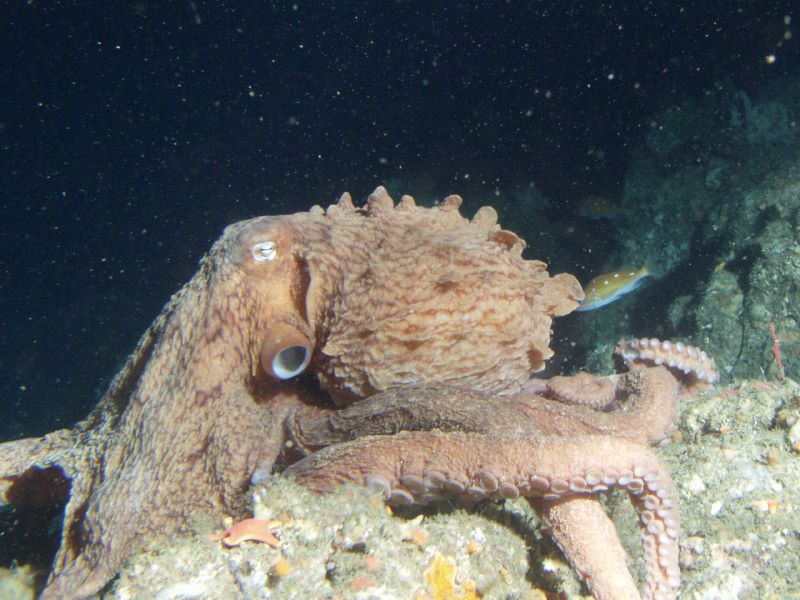

We can also talk about quite a sacrifice in the case of the giant Pacific octopus; a female tends to her eggs and constantly cleans them off of algae, among others. She does not leave the eggs even to hunt for food. In this gloriously tragic act of self-sacrifice, she dies of starvation and fatigue soon after her offspring hatches.

The Pacific salmon embarks on a no less life-threatening journey. This ocean fish is capable of travelling a distance of 3,000 kilometres to reach their freshwater spawning grounds in order to lay their eggs. ‘Such changes in morphology and biology of these animals—which for a significant part of their lives are sea creatures—cause the entire shoal of fish to die after spawning,’ says the USil researcher.

After the eggs hatch, a female giant Pacific octopus dies | Photo by Wikimedia Commons

A peculiar caring behaviour can be seen in strawberry poison-dart frogs, a species of amphibia found in South America. A female lays approx. 5-6 eggs at a time. After the eggs hatch, she transports the tadpoles on her back and can climb as high as 30 metres in search of plants called bromeliads. The plant has specific axils that fill with water; this is where the female places her offspring, each tadpole separately. She then comes to each tadpole every few days for 4-5 weeks and feeds them with her unfertilised eggs.

Orangutans are yet another species of caretaking mothers that invest a lot of their energy and time in the upbringing of their young. Females of this highly endangered species may nurse their offspring for up to eight years; this is one of the longest durations of nursing offspring in the animal kingdom.

When it comes to the offspring quantity, the record holders are certainly mice; they litter up to 10 times a year with as many as seven pups each, which is undoubtedly exhausting for the female body. On the other hand, the tailless tenrec, a mammal native to Madagascar, may boast a different quantity record of 30 pups per litter.

Motherhood in nature takes vastly different forms. We can observe various levels of investment in offspring nurturing among numerous fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals. It is worth noticing this remarkable evolutionary mechanism and appreciating moms of all species on Mother’s Day.