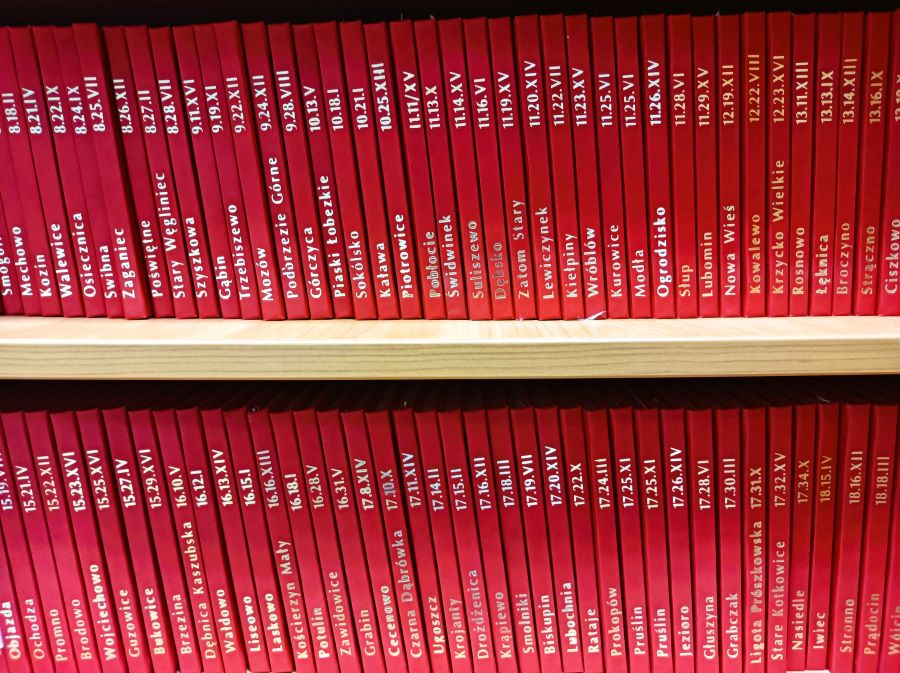

The Faculty of Arts and Educational Science of the University of Silesia, located in Cieszyn, is the only entity in Poland and Europe collecting ethnographic materials concerning Polish rural culture of the second half of the 20th century. The discussed collection – Archives of the Polish Ethnographic Atlas (PEA) – contains thousands of questionnaires, surveys, photographs, maps and other archival materials constituting a significant part of the Polish ethnological output. Most of them are paper notebooks, which over time began to degrade. The only means of protection against the loss of the collected data is its gradual digitisation, scientific development and publication on the platform Digital Archives of the Polish Ethnographic Atlas (paenew.us.edu.pl).

Thanks to the work of Cieszyn researchers, today one can virtually explore unique ethnographic records resulting from field research conducted throughout Poland for several decades. Without leaving their home, a modern Internet user can learn what wild plants were collected for food and medical purposes in different parts of the country, how the deceased were dressed and what a pregnant woman was forbidden from doing. So far, the staff of the atlas laboratory in Cieszyn has managed to digitise 15 thousand objects (data from 2024). They constitute six interesting ethnographic collections.

The largest project of Polish ethnology after World War II, which is still ongoing

The history of the Polish Ethnographic Atlas begins in the late 1945. At the 21st General Meeting of the Polish Ethnographic Society in Lublin, attention was drawn to the need to develop an ethnographic atlas covering the contemporary borders of Poland (including the western and northern territories). Over time, it was decided that the PEA would be based on a network of the so-called permanent research points (338 villages). The basis for the analysis was survey and field research, supplemented with data from ethnographic literature, museums and archives. Based on that, subsequent maps and commentaries were created over the decades, showing the cultural diversity of Poland in spatial form. To this day, 770 maps have been published (including PEA issues I–VI). The remaining, unpublished cartograms are located in the PEA Archives (issues VII–IX).

How did the PEA Archives end up in Cieszyn? The PEA materials, owned by the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology of the Polish Academy of Sciences, were transferred from Wrocław to the Cieszyn branch of the University of Silesia (currently the Faculty of Arts and Educational Science) in 1998 in order to continue the work on the Atlas. Since 1998, the formal curator of the collections and the head of the PEA Laboratory was Zygmunt Kłodnicki, who, with the help of students, completed the field studies in north-eastern Poland. Under his editorial supervision, seven volumes of the “Commentaries to the Polish Ethnographic Atlas” were developed in the years 2002-2013, devoted to folk knowledge and beliefs, birth and wedding rituals, and neighbourly help. In 2017, Agnieszka Pieńczak took over the atlas collections, and three years later Anna Drożdż became the editor of the “Commentaries to the Polish Ethnographic Atlas”.

The collections of the PEA Archives in Cieszyn are rich and diverse. They comprise thousands of questionnaires, surveys, photographs, maps and other archival materials constituting a significant part of the Polish ethnological output. The largest amount of source data was obtained from interview questionnaires covering twelve main topics, on the basis of which research was carried out for over four decades (!). Within the atlas materials, one will find interesting information on the everyday life of villagers not only in the so-called indigenous Poland, but also in the areas where cultural continuity was interrupted as a result of post-war changes (the so-called western and northern territories). Most of these archival materials have unique documentary value, but are still widely unknown in scientific and non-scientific circulation.

Since 2014, thanks to further funding from the Ministry of Science and Higher Education, under the National Programme for the Development of the Humanities, long-term work has been conducted under the direction of A. Pieńczak. The activities were related to the gradual digitisation, scientific processing and sharing of PEA materials on the website of the Digital Archives of the Polish Ethnographic Atlas (paenew.us.edu.pl). The research endeavours undertaken for a decade have been aimed at protecting and preserving the knowledge about the cultural heritage of the Polish countryside by making the PEA Laboratory materials available to a wide audience. The Polish Ethnographic Atlas can therefore be described as the largest project of Polish ethnology after World War II, which is still ongoing.

Photo by A. Pieńczak

Photo by A. Pieńczak

“Comfrey on the balks or in other places will be looked after…”

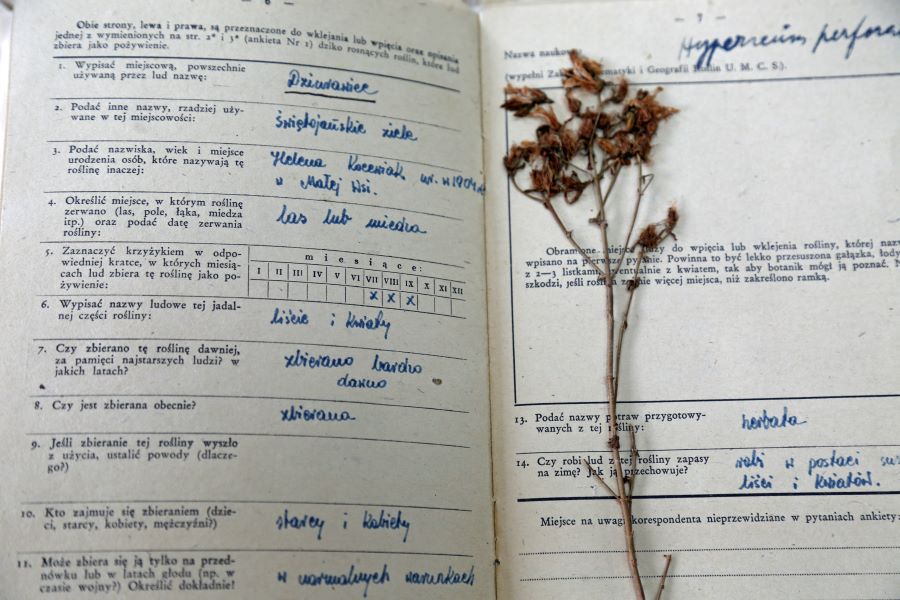

A significant historical and cognitive treasure among the atlas collections are the questionnaires on collecting wild plants for food and medical purposes, often containing herbarium specimens. It is an ethnobotanical collection acquired in a systematic manner (therefore it is unique on the European scale) – the fact which has been repeatedly emphasised by an ethnobotanist Łukasz Łuczaj. The questionnaires are a result of the first atlas studies conducted initially by the Polish Ethnographic Society. These are the oldest materials (from 1947 to 1953) collected in 239 localities, with the use of special questionnaires sent to representatives of selected villages (e.g. village heads, clergy, officials or people of other professions). Four questionnaires were sent to each of them, but not all of them were returned. The quality of the material obtained in this way varies (some questionnaires were partially completed, some were empty), but despite the gaps, a significant amount of valuable information was collected on the use of wild plants by the villagers.

For example, in the village of Sielsko (near Łobez), around 1948, children still used to collect pigweed (Chenopodium album), known in the village as “wild sorrel”. During World War II, this plant was the starvation food of the villagers. It was used to prepare soup and seasoning for potatoes; however, it was not part of the winter stock up process. In the village of Borsk (near Chojnice), during a similar period, a decoction of dried comfrey roots (Symphytum officinale L.) was used as a proven remedy for coughs, hoarseness, blood spitting, as well as stomach and bowel ulcers, and its leaves were applied to wounds that were difficult to heal.

Most of the discussed questionnaires were in poor physical condition, indicating advanced degradation. Many of them were very dirty, yellowing, with visible streaks, tears and gaps, some plants crumbled. Conservation work on such delicate material was complicated and included, among other things, disinfection of the objects, preparation of photographic and descriptive documentation, dismantling of the questionnaires, ripping up the blocks, disconnection of the plants, mechanical cleaning of the cards, their deacidification, straightening and filling of the gaps, arranging them in folds, sewing in accordance with the original arrangement, strengthening of the plants and placing them on the appropriate cards and making protective boxes for storage. In this way, the collections were saved from progressive destruction and they were digitised and published on the platform Digital Archives of the Polish Ethnographic Atlas for dissemination purposes. Currently, we can observe a surge of interest among the public in broadly understood survival, including natural methods of collecting and healing.

“There is a well-known belief that death is heralded by a howling dog…”

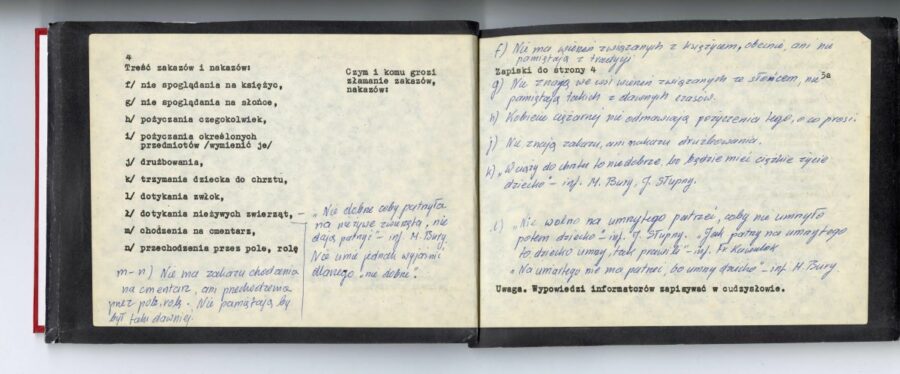

Materials devoted to birth and funeral rituals have also been deposited in the Cieszyn archives. The first include 339 PEA questionnaires entitled Birth customs, rituals and beliefs (1969–1976). Each notebook contains questions addressed to residents of selected villages, concerning various beliefs, practices and behaviours related to the child. The questions cover several broad issues, including isolation-related prohibitions applied to pregnant women and women in labour, magical activities aimed at facilitating childbirth, divination about the child’s gender, the role and significance of the folk midwife, customs related to christening, motives for choosing godparents and religious stories about the origin of the child and the parents frightening the child. For example, in Istebna (near Cieszyn), it was believed that a pregnant woman could not look at a fire, so that the child would not have “red spots” (birthmarks) on its body, and naughty children were scared with the so called bebok that could snatch them away (the description indicated that it was a supernatural being without a head, with one leg of a chicken and the other of a horse).

The second discussed collection consists of 349 PEA questionnaires entitled Funeral customs, rituals and beliefs (1969–1977). Each of them contains questions about various beliefs, practices and activities related to funeral rites in the broad sense. The questions cover several topics, including: death heralds, ways of easing the death, folk ideas about death and the soul, clothing of the deceased, their equipment, keeping watch over the corpse, customs related to taking the corpse to the cemetery, post-funeral refreshments, mourning, care of the grave, coffin. For example, in Rybno (near Wejherowo), it was believed that death was announced by a dog howling with its head to the ground, similarly to a raven, an owl or a cawing crow circling the house. One can also learn that in the past in this village, a snuffbox with snuff and a pipe with tobacco were placed in the coffin of a deceased elderly man, and a cap that he wore during his life was placed on his lap.

It is worth emphasising that each notebook contains the same questions, so the obtained data is comparable. Detailed answers were not always obtained, however, despite this, a lot of interesting data on birth and funeral rituals in the second half of the 20th century was collected in various parts of Poland. Some of the interviewees’ memories dated back to the beginning of the century, which increases the uniqueness and documentary value of the ethnographic materials obtained in this way.

Most of the discussed questionnaires were not in good condition. This was mainly due to the use of acidic paper for their production, which, over time, caused the pages to yellow and the material to weaken. The age of the paper, frequent use and previous exposure to excessive sunlight in the PEA Laboratory had made the covers of many of them torn, and the names and village references – once written in pencil or marker – became illegible. Conservation work first consisted of mass deacidification of these and other materials in the Paper Clinic in Krakow, which stopped the degradation of the paper. The next step was bookbinding, which consisted in strengthening the whole by adding new, hard covers and embossing the correct references and names of towns on their spines. After digitisation, the collections were assigned new inventory numbers and entered the database of the Digital Archives of the Polish Ethnographic Atlas (October-December 2023).

Photo by A. Pieńczak

Photo by A. Pieńczak

“The stork is a transformed man…”

The atlas activity consists of documenting (obtaining material as part of field studies, museum and library research) and interpreting the data (developing taxonomies covering various forms and varieties of phenomena, creating maps and drawing conclusions based on them). The result is the systematically arranged data, which is applied to base maps (usually with the use of the point technique), showing the cultural diversity of the investigated phenomena in a spatial and chronological form. The maps illustrating the vitality of cultural phenomena are particularly valuable, however, sometimes they cannot be developed.

As part of the work, over 1,000 atlas maps have been developed so far, showing selected aspects of the Polish village culture in the second half of the 20th century. Many of them have been published (770 maps). The aim of the undertaken digitisation activities was to create a single, coherent collection of the maps published so far. They contain various elements of village culture. 770 maps from two sources have been planned for digitisation and scientific elaboration. The first comprises seven atlases published by the Institute of the History of Material Culture (372 maps), containing mainly maps related to agriculture, breeding, construction, food, clothing, transport and other artifacts. An example map concerns the location of cellars and the range of the occurrence of the name “sklep“ (“shop”), which used to mean a cellar under a building (map 176, sheet LXXXVI). The map provides information about, among other things, places in Poland where cellars under buildings prevailed, and where free-standing ones were more often located. The second source of data are the maps published in the series “Commentaries to the Polish Ethnographic Atlas” (398 maps), mainly related to folk beliefs, neighbourly help, and family rituals. One of them, for example, illustrates beliefs regarding the origin of the stork. In some parts of the country, it was said that the stork had been created from a human (map 45, “Commentaries on the Polish Ethnographic Atlas”, Vol. 6), who, as a punishment for his carelessness (e.g. excessive curiosity), was transformed into a bird. That is probably why the stork was addressed by a human name (e.g. Wojciech).

Objects which are often no longer present in the cultural landscape

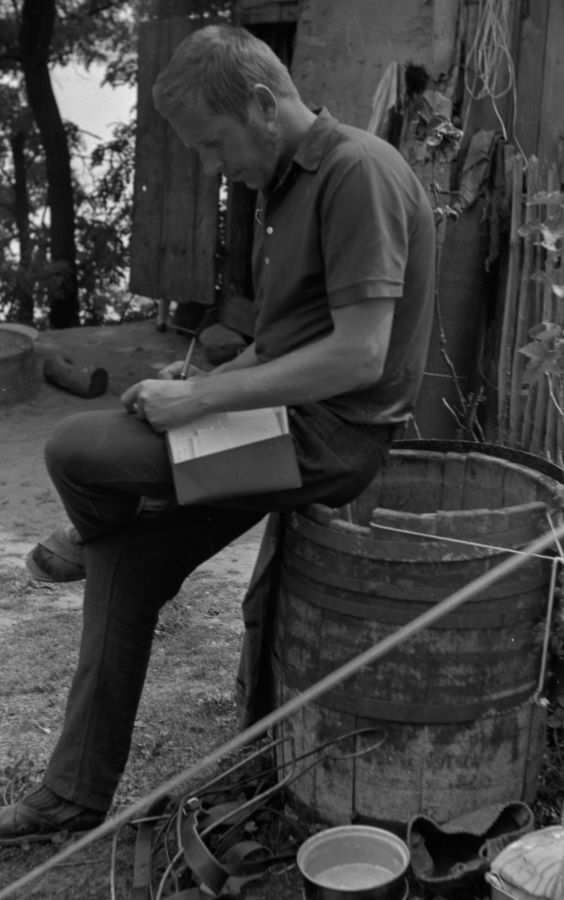

The Cieszyn atlas laboratory also houses two extensive photographic collections. The first comes from many years of field research (1954–1971) and consists of 12,181 small inventory cards containing black-and-white photographs. The photographs, taken by over 60 people, mostly concern material culture –wooden carts, forms of horse-drawn carriages, farm tools and traditional rural architecture. In the case of this collection, conservation work was indispensable – it was necessary to clean the inventory cards using specialist sponges and erasers, to glue photographs that protruded from the cards using glue based on an acrylic and water solution, to remove metal, often rusty staples with which some of the prints were attached. These activities allowed for the later digitisation, digital editing and publication of the collection (May 2015 – November 2016).

The second collection results from many years of ethnographic interest of Professor Zygmunt Kłodnicki, an expert in the culture of the Polish countryside in the second half of the 20th century. It is part of the researcher’s general private photographic archive (1,198 items were selected for digitisation). The photographs were taken during his private field trips, sometimes during atlas research (1960–1987). Some of them feature the members of the researcher’s closest family, his acquaintances and friends. The author documents the everyday life of the Polish countryside, including the traditional elements that were still in use (such as construction, agricultural and fishing tools), and sometimes draws attention to the contemporary contexts of life in socialist Poland. In the case of this collection, no prior conservation work was necessary – the materials were well-preserved by the owner in special dust jackets intended for storing negatives.

The photographic collections discussed here have a unique documentary value, as many of the objects recorded in them no longer exist in the cultural landscape of the Polish countryside.

Plans for the future

A large part of the documentation available in the PEA Archives in Cieszyn is waiting for scientific elaboration. The plans for the coming years involve digitisation, digital editing and online publication of nearly 1,000 extensive questionnaires devoted to folk material culture, wedding rituals and folk demonology (depending on the obtained funding). Introducing this data into the database of the Digital Archives of the Polish Ethnographic Atlas will provide access to almost 130 thousand pages of additional unique ethnographic records from various parts of the country. It is worth emphasising that the documentary value of the atlas materials seems to be particularly important for preserving knowledge about the cultural heritage of the Polish countryside – both for local communities searching for the sources of their own cultural roots, and for various researchers dealing with the culture of the Polish countryside. Thanks to this, the Polish Ethnographic Atlas is becoming increasingly recognisable among people interested in the cultural diversity of Poland in its historical aspect.

Translation: Agata Cienciała

Proofreading: Anna Białas

Prof. Agnieszka Pieńczak | Photo by Matylda Klos