| Maria Sztuka |

There have been many studies on Holocaust and WWII. However, 76 years after the end of Second World War, the subject still remains a focus of research interest. New papers, monographs, articles and biographical sketches of former concentration camp prisoners appear in bookshops; correspondence from KL Auschwitz-Birkenau, Majdanek, Dachau and Ravensbrück is also regularly released.

Listy z lagrów i więzień. 1939–1945. Wybrane zagadnienia (Letters from concnetration camps and prisons) was published by Księgarnia św. Jacka in 2019. The author of the publication is Prof. Lucyna Sadzikowska from the Faculty of Humanities of the University of Silesia. The researcher’s interest in personal document literature began with her doctoral thesis (defended in 2013), whose subject was the mystical aspect in the post-war writings of Gustaw Morcinek. It is important to stress the fact that the supervisor of the doctoral thesis was Prof. Krystyna Heska-Kwaśniewicz, the curator of Morcinek’s writings and researcher who brings back the writer from Skoczów to his rightful place in Silesian and Polish literature.

‘Reading the books such as Listy spod morwy, Dziewczyna z Champs-Élysées, Listy z Rzymu, Siedem zegarków kopidoła Joachima Rybki and Judasz z Monte Sicuro completely changed my perception of the author of Wyrąbany chodnik. These shocking works had a profound effect on me. I knew that the next thing on my reading list must be Morcinek’s letters from the concentration camp, as that was where the roots of his sensitivity and the way he saw the world came from. The author of Zagubione klucze was an outstanding epistolographer. His correspondence from concentration camps turned out to be shocking. It opened up a different and totally new perspective on the perception of the writer. It also became a key to read his post-camp works,’ admits the researcher.

The effect of her cooperation with Prof. Krystyna Heska-Kwaśniewicz was joint publications, including Listy z Dachau. Gustaw Morcinek do siostry Teresy Morcinek (2016) nominated to Historical Book of the Year Awards of Polityka magazine, Głosy z „Ostatniego kręgu”. Korespondencja z Konzentrazionslager Auschwitz Józefa Kreta i Zofii Hoszowskiej-Kretowej (2020) and Działalność poselska Gustawa Morcinka, czyli katalog ludzkiej biedy. Prof. Lucyna Sadzikowska’s interest in the works of the writer from Skoczów also resulted in the book entitled Szukanie kluczy. O literaturze poobozowej Gustawa Morcinka (2017).

The implementation of Miniatura grant from the National Science Centre (2018) allowed the researcher to search the archives of former concentration camps: Dachau, Majdanek, Stutthof, Auschwitz, Gross-Rosen, and carry out a series of meetings with former prisoners.

‘My first interlocutor was Alina Dąbrowska, an amazing person, an invaluable treasury of knowledge and a former prisoner of five concentration camps. It is thanks to her that I reached many other former female prisoners. Unfortunately, Mrs Alina died last August,’ says Prof. Lucyna Sadzikowska.

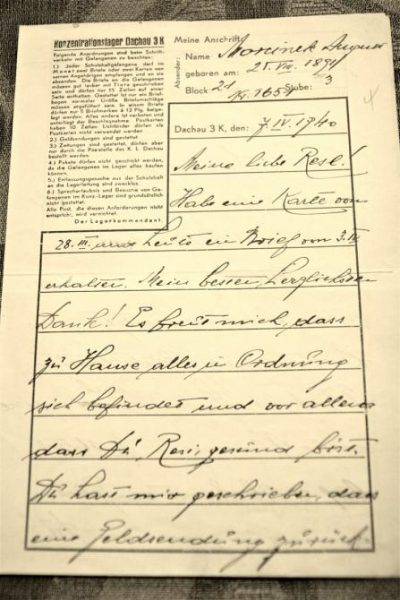

In the opinion of the literary scholar, the archives of former camps need to be ordered and introduced into a uniform system. It is necessary to create a straightforward information database, which will not only facilitate access to documents, but also save them from oblivion. Only a small part of the materials have been digitised, whereas the yellowing, delicate paper and discoloured, gradually less legible handwriting may soon make these valuable keepsakes impossible to read.

A majority of correspondence written by former prisoners is still privately owned. Many families keep the letters like relics. Some of them have been irrevocably lost. This is why the monograph by Prof. Lucyna Sadzikowska is so important. Not only does the author publish formerly unknown letters; she also asks the readers to reveal them and let them be copied.

Letters more precious than studies

Within the vast body of literature describing the drama of being closed in concentration camps, the letters written by and to prisoners form the polyphony of camp epistolography. The greatest value of correspondence is its authenticity.

‘The letters hide individual tragedies. Once we get deeper into the correspondence of specific prisoners, their tragedies become real to us, because they display the truth in the full extent of its cruelty. Watching the reality through the eyes of one man is much more convincing than perceiving it in the perspective of mass extermination. The performative nature of these egodocuments is revealed,’ explains Prof. Lucyna Sadzikowska.

Most numerous are letters to families. Setting them in a chronological order allows us to reconstruct a particular person, based on their emotions and facts. A thorough study of words full of warmth, cordiality and fear for the life of relatives creates a bond between the reader and the writer. It is no longer an anonymous prisoner, one of million victims of KL Auschwitz, but Franciszek Ogon from Rybnik, who dreamt about the day when he would hug his beloved wife and kids. Although he lived to see the liberation, but not to meet his family.

The need to write letters resulted from the will to keep in touch with the world outside the bars, the sense of obligation to inform the relatives about their own condition and camp reality (unofficial letters), as well as the inner duty to communicate about the bestiality of torturers. Correspondence with the relatives was also the act of mental transfer to the places close to the prisoners’ hearts, safe and carefully preserved in memory, which felt like balm for the soul during a short moment of writing. However, all of this resulted from the need to mark the existence in the world not divided by the barbed wire of the camp. The unofficial letters are overfilled with despair, which is far from ostentation and pushiness. Paradoxically, in the light of death, they affirm life and teach us respect to it,’ emphasizes Prof. Lucyna Sadzikowska.

Epistolography provides a lot of valuable information. It is characteristic for the senders whose attitude towards constant death threat was shaped by the family and the environment where they grew up. Therefore, the letters are also become a source of knowledge about specific local communities, their past, mentality, nature of family and neighbour relations etc. The way prisoners reacted to the camp reality was a result of the values they had taken from their family homes.

How are letters written from behind the barbed-wire fence different from even the most extensive memoirs published years later? ‘The experience is authentic,’ answers the author of Listy z lagrów i więzień. ‘Detailed accounts made after many years are charged with a narrative compiled (less or more consciously) from your own experiences, the interviews you have read, the accounts of other prisoners you have heard, the researchers’ comments etc. This is why the value of preserved epistolary materials is never undermined, and their emotional aspect is most valuable. Letters also allow us to get to know the experiences and emotions of people writing to their relatives closed in death factories. In epistolary dialogues you can either literally read or guess the encrypted messages or information about events in the camp. Not talking about certain topics is also meaningful. It would be interesting,’ the researcher emphasizes, ‘to determine what happened e.g. to the letters of Tadeusz Borowski, and how much of their content made the its way to his short stories.

The official letters could only be written in German (Polish language was forbidden). The authors were fully aware that if any censorship changes were to be made, they would be severely punished. Therefore, they had to limit themselves to safe, sometimes cliché statements. Some of them, though, still managed to include sophisticated encrypted messages, which camp censors were unable to decipher. Most precious are the unofficial letters with dramatic calls for help, because they document the crimes committed against the prisoners. It is invaluable research material for scientists. According to the author of the monograph, personal documents are capable of capturing the individual perspective, which is fundamental in humanities. Original letters from prisons and camps are part of the personal document literature category, referring to the notion of memory understood as private memory, not always identical with the official data and historical image,’ claims the literary scholar.

‘If correspondence from concentration camps and prisons provided with relevant commentary was properly and unobtrusively conveyed to young people, it would be a much stronger message than many fact-based narratives. Horrifying as they are, dramatic statistics are just numbers,’ concludes Prof. Sadzikowska.

The article entitled ‘Letters from the antechamber of hell’ was published in the November issue of „Gazeta Uniwersytecka UŚ” (University of Silesia Magazine) no. 2 (292).

Prof. Lucyna Sadzikowska from the Faculty of Humanities of the University of Silesia in Katowice | photo by Julia Agnieszka Szymala