Decarbonisation is a hot topic present in the centre of public discourse in many countries. The research conducted by Marta Tomczok, PhD, DLitt, Associate Professor, shows how large a role culture can play in taming decarbonisation.

Contact

Marta Tomczok, PhD, DLitt, Associate Professor, Institute of Literary Studies, University of Silesia – marta.tomczok@us.edu.pl

| Tomek Grząślewicz |

The fossil fuel extraction era in the Upper Silesia and Zagłębie region is coming to an end before our very eyes. However, coal is here to stay, as evidenced by heavy metal laden heaps and land subsidence. The research conducted by Marta Tomczok, PhD, DLitt, Associate Professor, shows how large a role culture can play in taming decarbonisation.

Decarbonisation, i.e. the process of reducing CO2 emissions, is a hot topic present in the centre of public discourse in many countries. In Poland, the debate temperature reaches scorching-hot levels. Perhaps the limited interest of authors and cultural practitioners who could convey valuable information to the public is to blame. The British films Brassed Off (1996) and Billy Elliot (2000) successfully depicted social unrest related to mine closures and miners’ strikes. A few years ago, Germany officially concluded their coal extraction era in the Ruhr area by organising multiple initiatives, ranging from exhibitions to official ceremonies involving politicians. According to the scientist from the University of Silesia, in recent years Polish culture took a big step towards departure from the current coal-related problems.

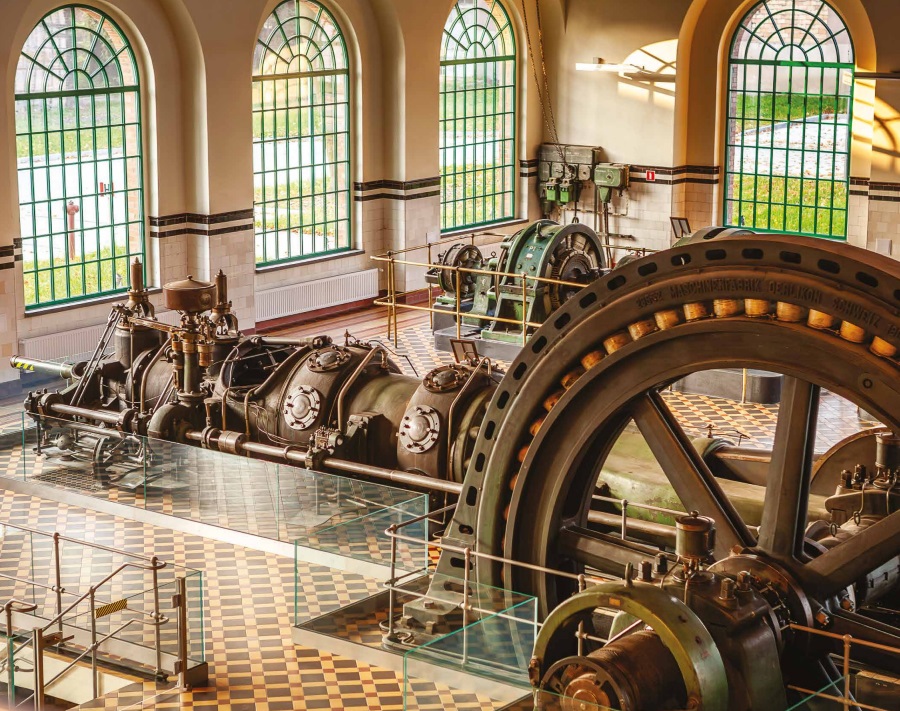

Elektrownia Gallery of Contemporary Art in Czeladź | Photo: Rafał Opalski

‘We are in need of good transformation narratives, which could introduce us to the transition process from coal fueled electricity to nuclear energy. Last year, the Ministry of Climate and Environment released a radio advertisement about the Atomicki family. It was only broadcast briefly, but certainly helped improve the image of nuclear technology in the eyes of the society. This is a good example of the so-called energy culture. For many years, the industry of Silesia and Zagłębie region inspired authors, who would present the impressions of their stay in this mining region to readers right away, while they were still hot of the press. The image of industrial Sosnowiec at the end of the 19th century shown in The Homeless by Stefan Żeromski became quite iconic. When modern writers — such as Szczepan Twardoch or Zbigniew Rokita — take up coal in their writing, they refer primarily to its past. Female writers are more engaged in current decarbonisation issues. Magdalena Okraska and Agata Listoś-Kostrzewa describe cities deformed by the industry in Silesia and Zagłębie. Maja Wolny pictures an apocalyptic vision of the future, warning us of the dangers of nuclear power. Anna Malinowska, on the other hand, advocates for the revitalisation of Katowice while preserving the memory of the city’s industrial heritage. The researcher from the Faculty of Humanities favours the latter idea, pointing out that Silesia and Zagłębie Dąbrowskie should further develop or create institutions with sufficient space for different narratives about coal.

‘The Guido Coal Mine and the Queen Luiza Adit in Zabrze are both excellent, but they lack an educational and informational component, multimedia content, and above all a historical trail for children’, believes Prof. Tomczok. ‘You can get a taste of being in a training mine there, but all the knowledge and narration about history is provided by a guide. The Coal Mining Museum in Zabrze, which boasts long-standing tradition and plentiful resources, still isn’t open to the public. I have high hopes for the Saturn mine in Czeladź, where I find freedom, space, and a certain mysticism. I also like the Sztygarka mine in Dąbrowa Górnicza, which shows the intellectual, scientific, and anti-communist face of mining’

One of these facilities could become a space to present artworks and joint photography projects documenting the end of coal mining in Silesia and Zagłębie. Arkadiusz Gola, Marek Locher, and Maciej Mutwil know how to capture the atmosphere of this important historical moment — from the work of the last mining crews, through the empty interiors of the mine, to the demolition of the shafts. Their photographs would go well with the street art by Mona Tusz, the significance of which is emphasized by Prof. Tomczok. They feature Silesian landscapes and references to their industrial past, yet are often dominated by plants. After all, they now overgrow the cement plant in Grodziec or the Paciorkowce heaps in Bieruń — places frequently visited by the researcher.

‘I would like our writers to visit Grodziec and see for themselves what it looks like today’, says the researcher. ‘I would like to read a piece or see an artwork telling us how the land changes here and what happens to the industrial ruins: that it does not turn into a rust belt but into large fields of green overgrowing the rust and the collapsing steelworks, cement works, and brickyards. I wish this work returned the environment and rivers to people, and invited them to relax and enjoy nature. We should start redefining transformation and stop thinking about it only in the anthropocentric way, i.e. that if we don’t invent it and spend European funds on it, there will be no change. These changes are taking place constantly, we just don’t see tchem.

The historical building complex of the former Saturn mine in Czeladź | Photo: Rafał Opalski

The article entitled „Goodbye, coal” was published in No Limits no. 2 (8)/2023, the popular science journal of the University of Silesia.