| Małgorzata Kłoskowicz, PhD |

They are not picky. They like potatoes, beets, broccoli, and tomatoes. They won’t turn their noses up at ornamental plant leaves either. They can be invasive and very harmful from our perspective, and they are difficult to get rid of. Whiteflies, as they are called, are small bugs found in our country. Both their modern and fossil forms, trapped in amber, are studied by Jowita Drohojowska, PhD, DSc, Associate Professor, an entomologist from the Faculty of Natural Sciences at the University of Silesia.

Like White Ghosts

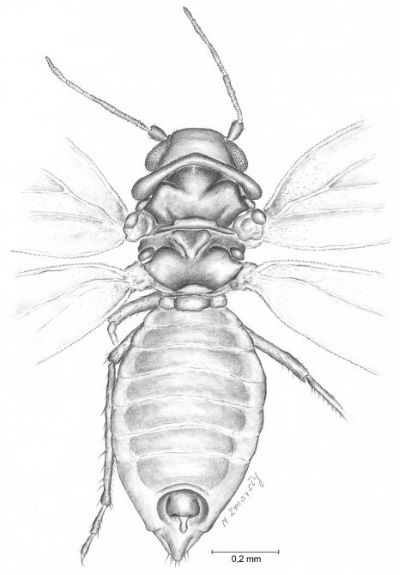

Whiteflies are inconspicuous insects whose adult forms are easy to recognise because they are very distinctive. It might seem like their bodies are covered in flour, hence their name. They resemble moths in appearance. Professor Jowita Drohojowska notes that even Linnaeus had trouble classifying them and mistakenly assigned the first described species to butterflies. However, they are actually the ‘true bugs’ (Hemiptera), as we know today thanks to much more precise research equipment.

‘We know of over 1,700 species of whiteflies distributed around the world. They are troublesome plant pests and are not picky. They feed on plants classified by botanists into over 140 families, which shows their reach,’ says the entomologist.

They can be found on the lower side of leaves. Using a special piercing-sucking mouthpart, they suck out sap while simultaneously excreting sugars. The sweet excretions cover the plant, clogging the stomates. Their presence promotes the growth of fungi on the plant, causing it to become diseased. Moreover, whiteflies can be vectors for various viral diseases.

‘From the breeders’ point of view, we are dealing with pests. But they are a difficult opponent. Their eggs are practically unnoticeable; it is only in the fourth larval stage, called the puparium, that a trained eye might be able to spot them. Bu then, it is usually too late’ explains the researcher.

‘That’s not all. Adult individuals can fly, and it must be admitted that they are really great fliers, capable of moving quickly. No wonder that currently, enormous funds are being allocated to research that would help effectively combat them. So far, however, the results are not very satisfactory’ comments the scientist.

Prof. Jowita Drohojowska is an entomologist. She is not involved in searching for new insecticides, but the results of her research will allow for a better understanding of these exceptional insects. She is interested in the phylogeny of whiteflies, meaning their developmental pathway: their origin along with evolutionary changes. She studies both fossilised and contemporary forms of these bugs.

‘Interestingly, the classification of the whiteflies we know today is based on the characteristics of the last larval stage. The morphology of adult individuals of many species is unknown, and in the few cases that have been studied, this morphology has not been thoroughly compared or used to understand the relationships between different groups of these insects. Meanwhile, the fossil whiteflies we know, with the exception of one species, are represented exclusively by adult forms’ says the biologist.

‘I decided to fill this research gap. Last year, I received funding for my project in the OPUS competition of National Science Centre, which was a pleasant surprise for me. Basic research, such as phylogenetic studies, is rarely selected for funding. In this case, however, they turned out to be important enough that I received the funds to carry them out.’

Amber Inclusions

As part of the project, the entomologist is conducting detailed studies of the morphological structure of adult whiteflies, both fossil and contemporary species. For her research, she has already acquired over 200 amber pieces with well-preserved whitefly inclusions from deposits in: Lebanon, China, Burma, France, Poland, Germany, Denmark, Ukraine, and India. These materials are dated from the Lower Cretaceous to the Late Neogene.

‘I don’t, of course, have a private collection of inclusions. The idea of this research is based on open acces to science. I obtain material for analysis from curators of insect collections around the world, who are always willing to share their specimens with scientists’ emphasises the researcher. She adds that sometimes interesting objects can be found on auction sites; however, good practice among scientists worldwide is to indicate in the article presenting the research results to which collection the material belongs and its catalog number. This ensures that others can always access it and verify the analyses conducted.

Jowita Drohojowska, PhD, DSc, Associate Professor | photo: Małgorzata Kłoskowicz

Like Linnaeus

Amber contains a wealth of information about insects, giving these objects a significant advantage over animal imprints in sedimentary rocks. When a researcher receives a new specimen, they first check the most important morphological features and assign it to a family, genus, and species. If they notice they are dealing with a new species or even genus, they begin by developing a diagnosis. The diagnosis should include a set of features indicating that it is a distinct taxon, different from those known so far. Distinct sets of features must be diagnostic for genera and species. They should also refer to similarities that suggest potential relationships between the distinguished taxa. Various modern microscopic and imaging techniques are used for this, and in the case of contemporary forms, molecular studies can also be attempted. Unfortunately, whiteflies are very problematic research subjects in this regard as well.

The next step is to document the observations using photographs, measurements, and drawings. A detailed description of the specimen, along with geological information about its origin, age, etc., is essential. If the specimen represents a new taxon, it is assigned an official Latin scientific name in accordance with the rules of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature. The subsiquent steps involve preparing the manuscript for publication and registering the newly created taxa in the ZooBank database.

‘The publication of a paper is a special moment. Even if a scientist passes away, the taxon’s name, their surname, and the year of publication remain. I have described over 60 new taxa to science so far, but I hope many more discoveries are still ahead of me’ emphasises the researcher.

She also adds that she once described a new superfamily in her lifetime, which is very rare in the field of contemporary entomology.

‘We were working with material from amber deposits in Burma. I started examining a specimen and noticed that it had a combination of characteristics from both whiteflies and psyllids. At first, I thought it was a mutant and that it was not worth spending more time on researching it. However, I later received similar specimens from collections in China and Lebanon. They all had the same unusual features. It couldn’t be a coincidence’ recounts the researcher.

‘We spent three years analyzing every detail. We conducted a phylogenetic analysis based on the morphological features of all known contemporary and fossil taxa of the suborder Sternorrhyncha. As a result, we ended up describing not only a new species and genus but also a new family, superfamily, and even a new superorder. This is an absolute rarity. When we sent the results to the journal, the paper was reviewed by seven experts who ultimately confirmed our discovery’ she emphasises.

Catapults and Wax

On a daily basis, entomologists focus on describing and classifying the features of newly acquired specimens. ‘Even though we rarely discover something entirely new, this work is interesting and very rewarding’ says Prof. Jowita Drohojowska.

‘Whiteflies are exceptional insects. Their adult form is characteristically white because their bodies are covered in… wax. I’ve already mentioned that they excrete large amounts of sugars. If these sugars were to cover their bodies, they would be at risk of fungal attacks’ explains the entomologist. They defend themselves in two ways.

Firstly, they have specialized wax-producing fields on their abdomen. They use their legs to spread the wax evenly over their entire body. The even distribution of the wax is also aided by a constriction between the thorax and abdomen, which makes the body more flexible. Secondly, they have a special apparatus that functions like a catapult, allowing them to shoot their waste as far away from their body as possible. They are assisted in movement by three pairs of walking legs and two pairs of wings. They gather food using a specialised piercing-sucking apparatus attached to the thorax.

Based on the results of the research conducted as part of the project, a special matrix of morphological features of whiteflies will be prepared. This matrix will allow for the analysis of the degree of relatedness between the studies species, with the presentation of a phylogenetic tree. This, in turn, will enable the tracing and characterisation of the evolution of specific morphological features and their significance in the classifications of these bugs.

The article ‘Tiny Creatures Trapped in Amber’ was published in the March issue of University of Silesia Magazine 9 (319).

Lukotekia menae Drohojowska et Szwedo, 2013 | Marzena Zmarzły