The political transformation after 1989 necessitated the development of post-industrial areas in Poland. Among other things, the potential for historical, educational, tourist and even natural qualities was recognised in the areas of former mines or steelworks.

Contact

Marta Chmielewska, PhD from the Institute of Earth Sciences of the University of Silesia – marta.chmielewska@us.edu.pl

| Tomek Grząślewicz |

The need for massive-scale development of post-industrial areas in Poland is linked to the effects of the post-1989 system transformation. At that time, dozens of obsolete and unprofitable factories were closed down. Then emerged the issue of how to properly develop the areas of former mines and steelworks. In the early 21st century, shopping malls were often built on these sites, and over time their historical, educational, tourist, and even environmental potential gained wider recognition.

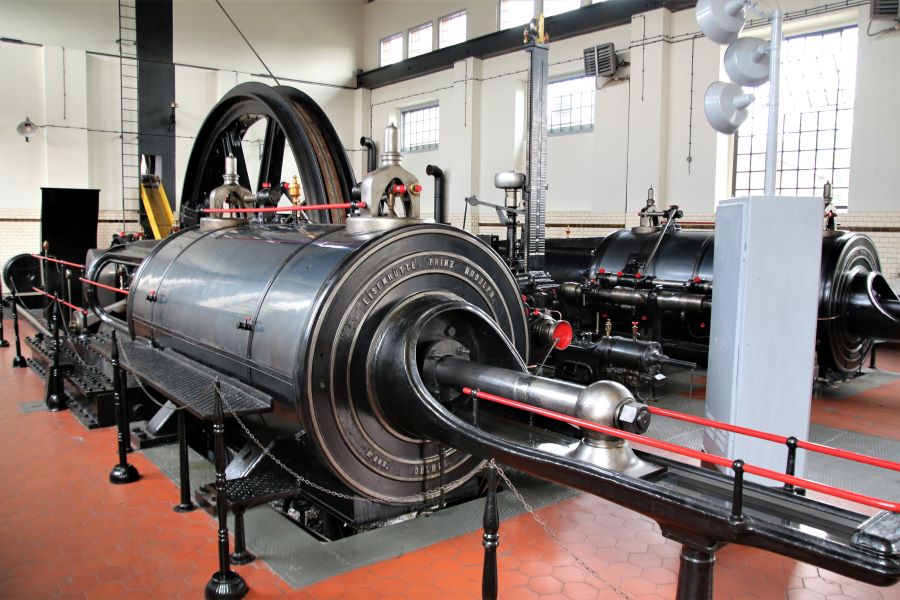

Queen Louise Adit complex in Zabrze | Photo by Tomek Grząślewicz

‘This is one of the oldest combined heat and power plants in Silesia’, says Marta Chmielewska, PhD from the Faculty of Natural Sciences of the University of Silesia, pointing to a facility located near the Queen Louise Adit complex in Zabrze. ‘It served both the mine and the developing town as a whole. This historic building has been taken over by the city and is meant to be used for tourism and to serve the needs of the local population.

In the 1960s, a part of Queen Louise mine (then known as the Zabrze coal mine) was excluded from mining activities, allowing for school tours to descend 503 metres underground to see how the mine operated. Subsequently, an open-air mining museum was opened there. Several years ago, it underwent a comprehensive revitalisation, understood as the transformation of the degraded part of the city, giving it new functions and taking into account ecological, economic, and social aspects. After two centuries of industrial development in Silesia and the Zagłębie Dąbrowskie region, there is no shortage of places meeting those criteria.

In Western Europe, the problem of how to properly manage areas left behind by former mines and steelworks entered the public discourse in the 1960s. ‘At that time, heavy industry plants began to decline in Great Britain, France, and the Ruhr area’, explains the scientist. ‘This brought the necessity to find a new way to develop these regions and stop the negative trends’.

Originally, the site of a decommissioned company was usually cleared of infrastructure and redeveloped. The breakthrough came with the impending closure of the Zollern mine in Dortmund in the 1960s. The desire to preserve the interesting architecture of the plant forced a change in the mindset regarding the heritage of the industrial age. Today, the Zollern site includes historic buildings, headframes, but also a catering facility and a playground for children. In Poland, a country operating under completely different economic conditions, the issue of revitalisation emerged later than in Western Europe. However, as the researcher from the University of Silesia points out, certain revitalisation measures began to be implemented long before it became trendy. ‘Years ago, in today’s centre of Katowice, there was a settlement called Kuźnica Bogucka, which hosted a small steelworks. Even before the settlement was granted city rights, i.e. before 1865, a park was established on the site of the steelworks. The Silesian Park in Chorzów and Stawiki in Sosnowiec were also created on post-industrial wastelands’, notes M. Chmielewska.

Queen Louise Adit complex in Zabrze | Photo by Tomek Grząślewicz

The need for large-scale development of post-industrial areas in Poland is linked to the effects of the post-1989 transformation of the political system. Dozens of obsolete and unprofitable factories were closed down. In early 21st century, shopping centres were often built on their sites, e.g. Stary Browar in Poznań and Manufaktura in Łódź. Although they succeeded in giving these places whole new lives, they also had a negative impact on the cities’ commercial function. No different was the Silesia City Center, which is considered the first comprehensive revitalisation project in the Silesian Voivodeship. Its three-stage implementation process resulted in a multi-directional change to the character of the area. Three former industrial buildings were preserved on the former coal mine site. More relics of the region’s mining past can be found in the Culture Zone, located in the immediate vicinity of Katowice’s city centre.

‘The Katowice coal mine operating there was closed down in 1999. There was much more consideration given to how to make use of the site than in the case of Silesia’, explains the researcher. ‘As a result, the approach was much more well-thought through’.

Unless they receive help through a grassroots initiative, the situation of post-industrial sites located in suburbs and remote districts is much more difficult. This was precisely the case with the Walcownia Museum of Zinc Metallurgy in Katowice-Szopienice where, after years of efforts by a dedicated association and organisations supporting it, a tourist facility was created and promoted.

Mining waste heaps are a special kind of legacy of the era of heavy industry. Some of them have grown into the city landscape and are used by the local population: for walks in spring and for sledding in winter. Mount Antonia in Ruda Śląska-Wirek has recently been revitalised and now offers many walking paths, barbecue areas, benches, and a mini playground. However, this is still a rare occurrence: as part of our landscape, it is more common to see mining waste heaps, which are often left abandoned. However, sometimes this kind of approach can bring very good results.

‘Nature is never idle. Spontaneous succession takes place when heaps are left alone: new, valuable species tend to appear, and biodiversity increases’, notes Marta Chmielewska.

Queen Louise Adit complex in Zabrze | Photo by Tomek Grząślewicz

In the Ruhr Metropolis studied by the scientist, the focus was initially on the planned (and costly) development of heaps. Many areas that once housed mining and production waste are now used for recreation, sport, and tourism. There are also landscape and theme parks. Some of these are further dressed up in such structures as bridges and viewing platforms. Given Poland’s ‘revitalisation lag’ in relation to Western Europe, it is worth asking ourselves the question of whether we should take inspiration from German efforts in this regard.

‘The fact that we are 30 years behind the Ruhr Metropolis means that we can benefit from their experience and avoid making the same mistakes’, claims Marta Chmielewska. ‘They also monitor the solutions introduced in Poland. They already know that sometimes it is worth letting nature take its course’.

The researcher mentions German projects that are worth taking a look at: the adaptation of post-smelting areas in Hörde, a district of Dortmund; the revitalisation of the Emscher river, which once looked like the Rawa river but now is a beautifully naturalised watercourse; and finally the Landscape Park Duisburg-Nord on the site of the former steelworks where you can take a walk through the green spaces between post-industrial installations.

Another part of the post-industrial heritage is the company-sponsored housing estates, built for the nearby factory workers and officials. In the Ruhr Metropolis, many of them have been restored; there is even a hiking trail connecting them. Katowice is proud of the Nikiszowiec district, Ruda Śląska of Ficinus, and Piaski in Czeladź has considerable revitalisation potential. However, there is no trail connecting them and there are many problems yet to be solved.

Company-sponsored housing estate in Czeladź, Piaski district | Photo by Tomek Grząślewicz

‘Some people are not even aware that they live in a former company-sponsored housing estate’, says the researcher. ‘When someone asks me to show them around Nikiszowiec, I always suggest going to Giszowiec as well, and preferably to visit the heavily degraded Szopienice or Borki and compare the differences’.

Then there is the social dimension written into the 2015 Revitalisation Act. Many worrying processes such as unemployment and various types of social pathologies are more common in the districts where heavy industry plants have been closed down. Local initiatives can play a huge role here, such as in the Załęże district in Katowice with its thriving district council and community centre, or in Rybnik where social engagement is built into revitalisation projects – citizens have the right to express their opinion on whether they like any particular idea or not. Local residents should also have the widest possible free access to the revitalised spaces within their neighbourhood. What does it look like in the case of Queen Louise in Zabrze?

‘Underground tours necessarily have to cost money because maintaining these places requires resources’, comments Marta Chmielewska. ‘However, we should bear in mind that the space we are in now is open and available to visit free of charge. We can take a walk there, visit an exhibition, and take a peek into some of the facilities’.

The growing awareness of the need to develop and manage post-industrial areas, as well as the creativity regarding the directions for revitalisation, is a positive development. The idea of building a gaming hub in Nikiszowiec fits in nicely with Katowice’s function as a creative place, which has been gaining traction for some time now. Another interesting example is the Porcelain Factory in Katowice, a place where new companies are moving in but simultaneously a place where you can also go to enjoy a concert.

‘I hope that we will move towards well-thought-out projects taking into account social, economic, and environmental factors. Sustainable development, which considers both advantages for the people who live in a given place and those who come every now and then to see a quality space to the sound of heavy machinery, is a safe bet to take. As it should be in a post-industrial site’, concludes Marta Chmielewska.

The article ‘Louise’s Second Life’ was published in the popular science journal of the University of Silesia No Limits no 2(10)/2024.