| Assoc. Prof. Jakub Morawiec |

The Viking epoch was an important time in Europe’s history, especially with regard to Scandinavia. A number of new phenomena, such as the centralization of power, far-reaching trade, and Christianization, contributed to significant political, cultural, and social changes in the entire Scandinavian region. They would not have happened if it had not been for the activities of numerous distinguished and charismatic persons. It is not surprising that the vast majority of them belonged to political and economic elites who could afford an unceasing and uncompromising rivalry for power due to having recourse to extensive military and financial means. Olaf Haraldsson, the Norwegian Viking, monarch, and saint, is a very good example in this context.

Olaf’s viking career

Information regarding Olaf’s early life remains unclear and has been severely distorted in the later hagiographic tradition. It is assumed that he was born around 995 and spent at least a part of his young life in Ruthenia. In then-contemporary accounts, Olaf is first mentioned at the point when he dwelt in England. There, he joined the infamous army of Thorkell the Tall which could not be vanquished and harried the country in the years 1009–1012. Similarly as Thorkell, Olaf made peace with Æthelred, King of the English, accompanied the latter in his exile to Normandy, and offered support when he was regaining power in his kingdom in 1014.

At that time, Olaf managed to demonstrate his prowess and efficacy as a leader, since he raided various parts of contemporary France and Spain. Moreover, Olaf gained his first political experiences in these years as well. This part of his life was marked by the most significant and far-reaching event, that is, his conversion to Christianity, which most probably took place at the Duke’s court in Rouen, contemporary France, in 1014. At that time, the jarl of Norway (jarl – the Scandinavian equivalent of the English earl) Eric of Hlathir (Eiríkr Hákonarson) participated in Cnut the Great’s conquest of England, and Olaf used this opportunity for an attempt to seize power in his homeland.

Olaf as the king of Norway

Olaf did not have enough determination, talent, or military and financial means to take over power from the hands of the Hlathir jarls, the main pretenders to the Norwegian throne. His status as a sovereign was mainly respected in the Southern and Eastern parts of the country. The powerful people from the West (above all the mighty jarl Erling Skjalgsson) remained neutral with regard to the new ruler or even showed hostility towards him. Olaf’s attempts to make them subordinate contributed to his eventual fall. The new King decided to use the Christian doctrine as the basis for his rule. An interesting fact is that while former accounts regarding Olaf’s reign focus on his missionary attempts, contemporary sources provide very little information on this issue. However, historians have little doubt that Olaf tried to introduce a new law in Norway, which was based on the principles of the Christian faith, and brought members of the clergy to the country. What is more, the ideological background accompanying his reign contained references to the concept of a just ruler (rex iustus) who introduces new laws and defends the subjects against all who break the law and stand up against the legitimate sovereign.

Olaf tried to strengthen his position in the region. Subsequently, he joined forces with the King of Sweden and attacked Denmark in 1026, however, Cnut not only managed to defend the country but also challenged the attackers in a naval battle which took place at the mouth of the Holy River in Southern Scania. From that moment on, Cnut became aware that the only way to maintain long-term supremacy in the region and power over his vast territory was to eliminate Olaf. In 1028, the King of England and Denmark left with a strong fleet for Norway and was supported by the local elites who still opposed Olaf. The latter one was well aware of the enemy’s superiority and found refuge in Ruthenia. He was accompanied by his son Magnus, who was almost five years old at that time. In 1030, Olaf gained knowledge about the disappearance of Hakon of Hlathir on the North Sea and decided to attempt to regain power in Norway. He reached his homeland the same year but had to face the local elites, who were financially supported by Cnut the Great. On 29th July, both sides faced each other at the Battle of Stiklestad. Olof was killed in combat, and Norway found itself again under Danish rule.

Saint Olaf – the development of his worship

In spite of what was traditionally claimed, it is almost certain that the worship of St. Olaf had been initially either stimulated or adopted by the Danish rulers of Norway. After the Battle of Stiklestad, Cnut chose to give the Norwegian throne to his juvenile son, Swen, who was accompanied by his mother and a group of experienced advisors. In order to strengthen Swen’s positions, they decided to present the young ruler as a spiritual successor of the late King who already at that time was becoming increasingly popular as a martyr and saint. This idea was not particularly original, as similar cases can be found in the history of tenth century Bohemia and England. However, it was of little avail to Swen. Around 1035, he and his mother were forced to flee the country.

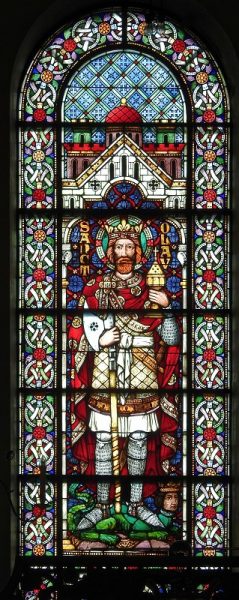

The Norwegian elites decided to pass the throne on to Olaf’s son Magnus, who had hitherto lived in Ruthenia. The new ruler based his reign entirely on his father’s worship. Olaf, who had become Rex Perpetuus Norvegiae (Norway’s Eternal King), was to be an exemplary Christian monarch for his son and the Norwegian people. Olaf quickly became the most popular and eminent saint of all Scandinavia. In 1053, Pope Eugene III decided to set up a new archdiocese in Nidaros (Trondheim) with St. Olaf as its patron. This fact significantly contributed to the emergence and development of writings dedicated to Olaf, including a few sagas and accounts regarding his miracles and martyrdom. Olaf was pronounced the entire kingdom’s patron saint. Whoever wanted to legally rule as a King of Norway had to recognize this saint’s unique status. Olaf’s symbol, an axe held by a lion, which is also the symbol of royal power, has been a part of Norway’s coat of arms until today.

Artykuł pt. „Święty Wiking” ukazał się w popularnonaukowym czasopiśmie Uniwersytetu Śląskiego „No Limits” nr 1(1)/2020.

Contact

Assoc. Prof. Jakub Morawiec

Institute of History University of Silesia, Faculty of Humanities

jakub.morawiec@us.edu.pl