|Małgorzata Kłoskowicz|

Scientists from the University of Silesia in Katowice have developed two solutions that will help in accelerating the process of obtaining new barley varieties by several years.

Years of research have resulted in a new method of isolating and initiating in vitro culture of microspores using an earlier developmental stage of spring barley.

“The subject of our interest was the process of androgenesis. It is an extremely interesting phenomenon that makes it possible to regenerate a plant from an immature pollen grain, i.e. a microspore,” says Monika Gajecka, PhD, co-author of the research from the Faculty of Natural Sciences of the University of Silesia.

Under normal circumstances, such microspores develop into mature pollen grains, i.e. into the male gametophyte. Pollination is necessary in order for the plant to reproduce, which in the case of barley involves the transfer of said pollen grains to the pistil. However, there is an alternative route that simplifies this process, which may be of particular importance in breeding varieties of economically important crops.

“We have the ability to change the pollen grain development route at an early stage. If we apply the right stress factors to the microspores, these immature pollen grains will not ripen but can still develop into a plant,” says the scientist.

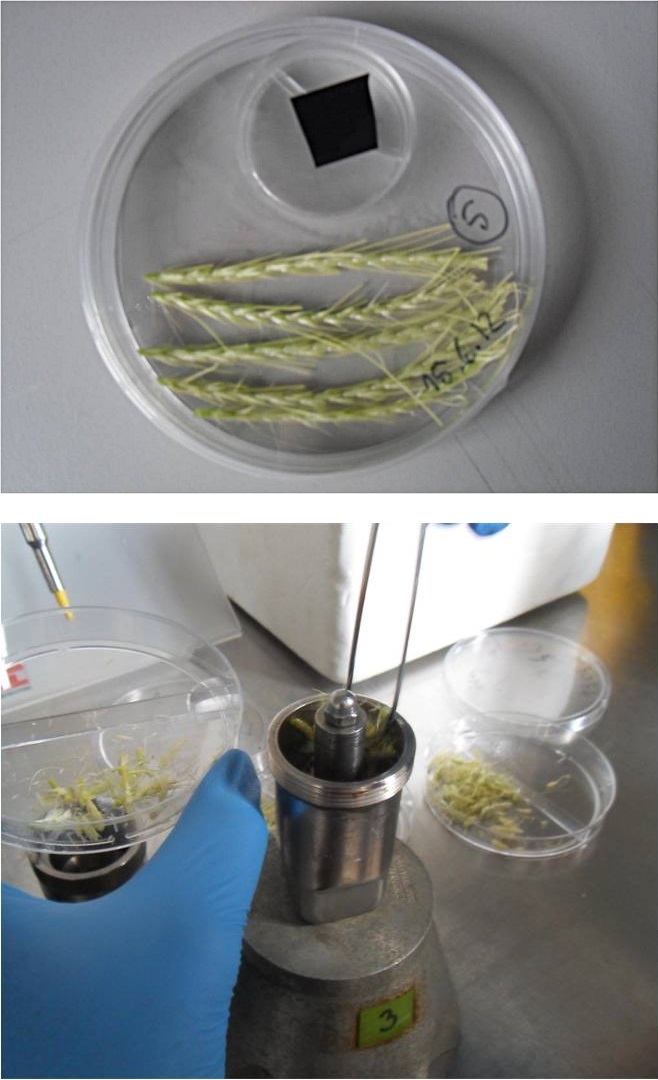

To achieve this effect, the biologists collect microspores that are at the right stage. They need an immature spike of barley, which is then subjected to two types of stress factors.

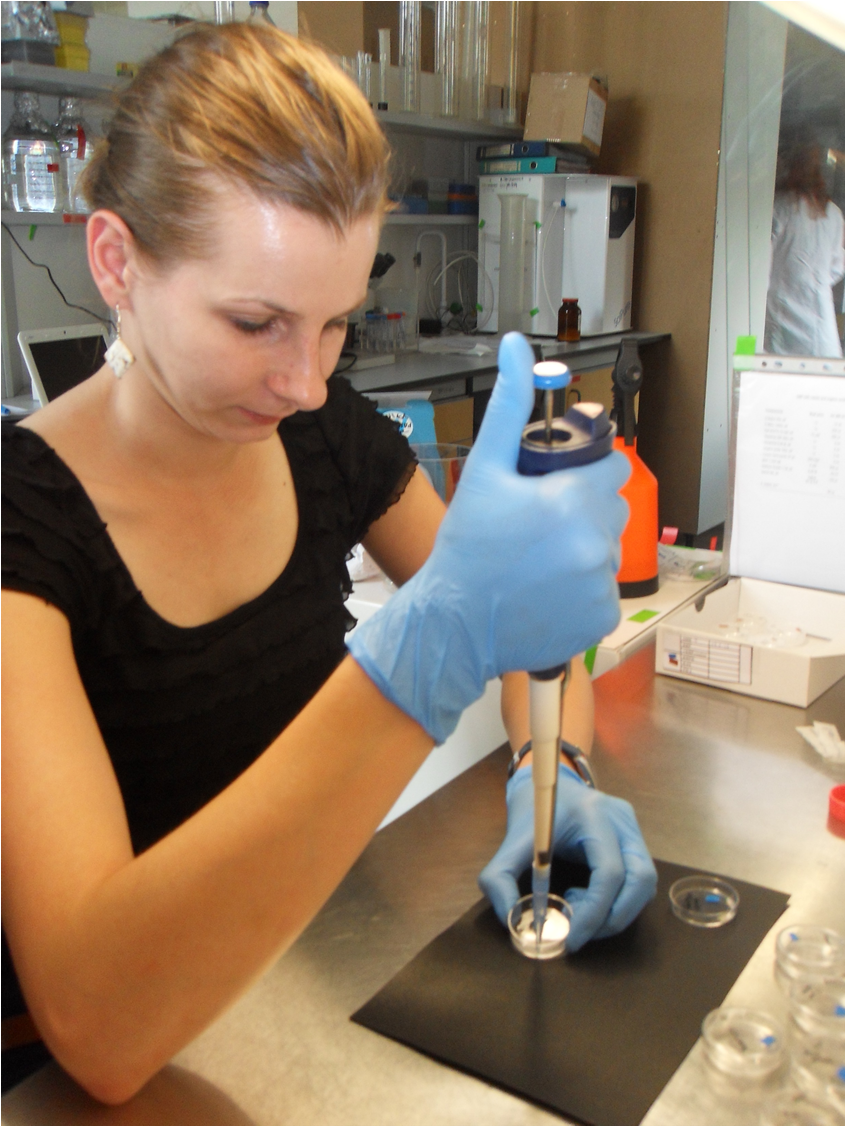

In the first type, the harvested ears are put into a refrigerator for two weeks to undergo supercooling. Then the immature spikes are gently pulled out of their sheaths and blended in a special device – in such a way as not to damage the microspores. This is what their isolation consists of. The next step is the initiation of the in vitro culture. Under controlled conditions, and by providing appropriate nutrients, the development of barley embryos is induced in the medium, then it is regenerated.

“The so-called specification of the plant takes place in the embryo, which means that a shoot appears in its apical pole and a root in its basal pole. This process, described in a very simplistic way, is what we call regeneration,” explains the scientist.

When it comes to the second approach involving a different stress factor, the sequence of steps is slightly different. From a freshly cut stalk of barley, the immature spike with its microspores is taken out, isolated and put into a properly prepared medium that only provides certain nutrients. In this case, there is no cooling phase, but instead the starvation of cells takes place.

This medium is then changed several times over the course of several weeks so that the development of the plant can be properly controlled, and after about 6 weeks we can observe the germinated embryos.

“In both cases we observe reprogramming, which results in obtaining a new plant from a microspore, not a mature pollen grain, as was the case with the naturally occurring process,” comments the biologist.

Photo from the private archive of Monika Gajecka PhD

“Our solutions are very important for plant breeding. Thanks to this process we are able to shorten the time needed to introduce new varieties of crops, such as barley. More specifically, by using the production of homozygous lines, which in microspore culture occurs spontaneously by doubling of the haploid microspore genome, we can shorten the tedious eight-year process to just two years. We skip one main stage of plant reproduction, i.e. fertilization and a several-year-long cycle of crossing,” emphasizes Monika Gajecka, PhD, co-author of the solution.

The scientists had to solve one more problem. The plants created in the in vitro culture should be green so that they can perform photosynthesis. However, during in vitro culture, the development of chloroplasts is often impaired at an early stage of differentiation. The resulting organisms are albinotic, white, lacking in chlorophyll, and thus unable to absorb nutrients on their own outside of the tightly controlled environment of in vitro culture.

“It is all determined by the genotype. Some varieties of barley will produce only green plants, others will produce only albino plants. Our aim was to find a solution that would allow all varieties to produce green plants capable of developing outside the in vitro culture. We have achieved this goal,” says Monika Gajecka, PhD.

The method of isolating and initiating the in vitro culture of microspores, developed by biologists, allows for producing green plants of all varieties, even those which in previous studies showed a very high level of regeneration of the so-called albino plants.

The stage of plant development in which the microspores are isolated and treated with a stress factor to reprogram them has turned out to be the key.

“Experiments carried out, also as a part of my PhD dissertation, written under the supervision of Prof. Iwona Szarejko, indicated what really determines the regeneration of albino plants. Plastids play an important role in this process. We initiated in vitro culture in specific moments of plant development. When the plastids had already differentiated into amyloplasts, then the plant regenerated in an albinotic manner. But if it did not happen yet, then we were able to obtain green plants. This was a breakthrough,” explains the researcher.

“When we discovered this key relationship, all we had to do was to determine the right moment for the initiation of in vitro culture. Thanks to that, now we can be proud of achieving impressive results of high regeneration of green plants, regardless of barley variety,” she states.

The solutions developed after many years of research have been protected by patents. The authors of the two inventions are: Monika Gajecka, PhD, Prof. Iwona Szarejko, Beata Chmielewska, PhD, Janusz Jelonek, MSc, and Justyna Zbieszczyk.

The researchers from the University of Silesia in Katowice have developed new methods for the isolation and initiation of in vitro culture of microspores using an earlier stage of development of spring barley, thanks to which the process of obtaining new varieties of spring barley can be accelerated by a few years. | photo by Monika Gajecka, PhD.