As a 7-year-old child he sees the events of 1905, keeping in memory not so much the workers’ rebellion as the implementation of what they were fighting for – the establishment of Polish-language schools. He uses this privilege and studies in his mother tongue legally. A few years later he takes part in the secret Strzelec section in his school. In 1915 he leaves school and joins the Polish Legions. Then forward to Szczypiorno, Polish Military Organisation, the border war with Ukraine, the war against Russia that he takes part in as a 1st Infantry Regiment officer. He is awarded the Virtuti Military Gold Cross and four times the Cross of Valour.

In September 1939, while searching for his military unit, he gets to Lviv, where he is arrested by NKVD in January 1940 and held in prison for 13 months, first in Lviv, then in Moscow, and finally in Saratov. He is liberated in July 1941 after the German-Soviet war breaks out. He immediately joins the Anders’ Army and reaches the Middle East with it. From there he is delegated to work in “W Drodze” journal published in Jerusalem. In 1945, he returns to Poland: to join his relatives and „(…) to work (…) serve for the common purpose – reconstruction” („Kurier Popularny”, 1945).

Who are we talking about? Władysław Broniewski. Literary scholars would be able to answer it, but those who took their Matura exam between WWII and late 1970s would probably find the question difficult. During that time, no official state ceremony could be carried out without poems written by the author of Mazowsze. All WWII anniversaries were mandatorily accompanied with: Bagnet na broń and Żołnierz polski; Pokłon Rewolucji Październikowej was read during the October revolution anniversaries, whereas obligatory poems for the 1st May processions included Pieśń majowa and Robotnicy – a standard repertoire of Polish communist propaganda, which ignored the whole military career of the author of Słowo o Stalinie. In the early 1980s, the interest in Broniewski’s works significantly decreased.

In research work by Maciej Tramer, PhD, DLitt, Associate Professor from the Institute of Literary Studies of the University of Silesia, author of monograph Literatura i skandal. Na przykładzie okresu międzywojennego (2000), the poet was featured in various configurations, but, as he explains, always in the background and on the side. Important encouragements came through the discovery of a rich and well-preserved archive deposited in the Władysław Broniewski Museum, a joint research trip with colleagues from the institute and a meeting with extraordinary curators: Sławomir Kędzierski and Regina Kaźmierczak. This opened up the possibility to read Broniewski not from the side of immovable print, but from the perspective of a manuscript, notes, unknown texts, documents and correspondence. The result was an extensive scientific publication entitled Brudnopis in blanco. Rzecz o poezji Władysława Broniewskiego (habilitation thesis, 2011), numerous articles, as well as critical editions of Pamiętnik (2013) and Publicystyka (2016) by Władysław Broniewski, and in 2021 five sketches about Władysław Broniewski entitled Wszystko zmienne (University of Silesia Press). However, the most visible effect was cooperation and meetings at different stages: conferences, exhibitions, publishing series, joint monographs, even consultations and scientific reviews. ‘Broniewski is simply a poet who must be shared’, emphasizes Prof. Maciej Tramer, and he adds: ‘Despite the established image of a propaganda poet, Broniewski is a disobedient, or even unpredictable person: forever a member of the Polish Legions, a rebellious “Republican soldier”, whose opinions become radicalised over time’. This is not a writer that could be described as “playing with words”. It does not mean that he had no sense of humour, which the author of Bar pod zdechłym psem proved many times. However, he thought that he had something important to do with his works. One can find there his disillusion with history, his anger with injustice, but also his faith in the possibility to repair the world and admiration for all those who are capable of dedication. This attitude involves a lot of naivety, but also and a special sort of energy. This simple way of describing the world still finds its readers.

Broniewski was always disobedient, but the history affected him from the youngest years. He did not read about the 1905 revolution, but witnessed it. At school he was attracted by scouting. In the junior high school in Płock he published “Młodzi Idą” magazine, although he was only 15. Two years later (still a minor) he used the Easter break to join the Polish Legions with his friends. This undertaking required a lot of courage.

‘It was a very hard decision – not only to escape from school, but also to act contrary to the local community of Płock, for whom joining the Austrian army, because this is how the inhabitants of Congress Poland perceived the Polish Legions, was seen as disloyal. We should also remember that the Legionists who were subjects of the Tzar risked death penalty for treason, if they were taken to captivity’, adds the researcher.

The 17-year-old boy joins the 4th Infantry Regiment. This is the beginning of a long complicated way and traumatic front experiences, which were difficult to handle by older and more experienced soldiers, and even more difficult for a student taken directly from school. He doesn’t understand everything, but he trusts his authorities. In 1918, he wrote in his diary: ‘I am a soldier under Commandant Piłsudski. For me he guarantees that I will serve for the good of my country and democracy.’ He takes part in fighting, but he also gets strongly involved in soldier councils. During the “oath crisis” in 1917, he has no doubt to join the rebels who unambiguously refuse to be loyal to any monarch. Broniewski serves in the 3rd Brigade which, similarly to the 1st Brigade, is referred to by the Legionists as a “civil army”. He continues to be a “Republican soldier”, highly politically-minded and prone to rebellion’, emphasizes the literary scholar.

In consequence, he ends up in the Szczypiorno camp, where he is a delegate in the soldier council and publishes the camp magazine. After release from prison, he gets involved with POW (Polish Military Organisation). He passes the Matura exam and begins studies in philosophy at the University of Warsaw. At the same time, he listens to news about soldier rebellions in Germany in November 1918 carefully and with hope. He takes part in disarming a German garrison in Warsaw. When Poland regains independence, he mostly identifies with the PPS (Polish Socialist Party) demands, and is enthusiastic about the 17 November decrees of Prime Minister Jędrzej Moraczewski, which provided equal rights for all citizens, established an 8-hour working day and gave voting rights to women.

‘However, sometimes little details tell us more than “big” facts’, claims Prof. Maciej Tramer. An example could be the stories related with the attempts to impose homogeneous uniforms in the Polish Legions. As a recruit in the 4th Infantry Regiment in Piotrków, Broniewski received a rojówka (a sort of horned cap, so-called after the name of the regiment leader). In his poems, he presents himself only in the “democratic” maciejówka cap.

His inconsistency can be found not only in his life choices, but also in his collections of poems. Broniewski attached much importance to the composition of his poetry volumes. His debut called Wiatraki consisted of eighteen poems selected out of almost two hundred. His archive even includes draft compositions, which show how the whole process was carried out. ‘The poet left nothing to chance’, notes the literary scholar. He carefully arranged and matched the texts. He would even write a new poem to fit the previously determined sequence. He never agreed to have his poems published in chronological order. Except for one case. In the first wartime volume published in Jerusalem in 1943, the first eight poems are arranged according to the dates when they were written. The first text is the title poem Bagnet na broń, written in April 1939. The work ends with a direct promise to fight until the last breath. However, the following poem in the volume is Żołnierz polski, created after the September disaster. Contrary to the declaration contained in the preceding poem Bagnet na broń, the Polish soldier returns here „from the German captivity”. There are more inconsistencies, as further poems tell about the poet’s stay in prison. Instead of any order we are faced with increasing incoherence. Is this the author’s inconsistency? The professor says “definitely not”.

‘This one-off chronological order served Broniewski to tell about paradoxes: historical, political, biographical. The poet did not think up this composition of eight poems, but decided to use it. He told a story, which is in fact a history scandal. There are more consistent inconsistencies like this. Broniewski was really unalterable. The poet’s archive contains a lot of documents that we are only now learning to read and tell about. Each of them requires careful attention and sensitivity. Part of it, for example the poet’s correspondence with his wife Maria Zarębińska, former prisoner of Auschwitz and Ravensbrück who died shortly after the war, requires respect, first of all’, ends Prof. Maciej Tramer.

The article entitled „Poeta nieobojętny” was published in the July issue of Gazeta Uniwersytecka UŚ (University of Silesia Magazine), no. 10 (300).

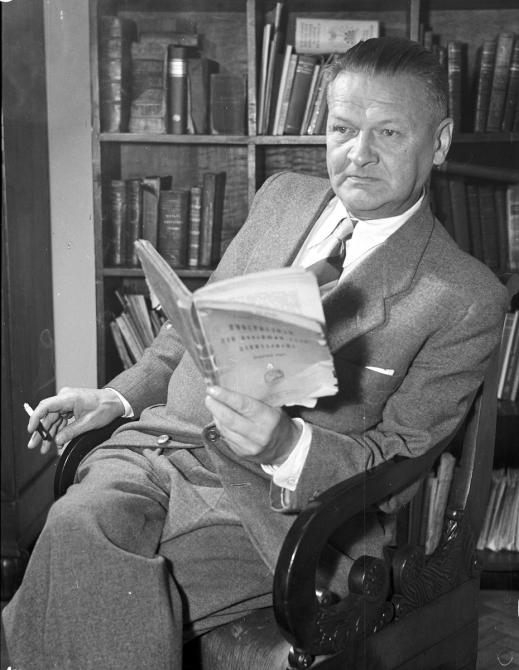

Władysław Broniewski | PAP/Radek Pietruszka