China and India are two ancient civilisations with amazing achievements. They were leading global powers until the industrial revolution. Then European countries dominated the world for over one hundred years, mainly in consequence of colonial conquests and industrialisation. The 20th century, in turn, brought the increased power of the United States, which joined the race of superpowers. From the perspective of the Chinese and Indians, those events were ephemeral, and these days the world is getting back to its proper shape.

‘People in Europe talk about emerging superpowers with reference to China and India, thus emphasizing certain surprise with the fast increase of their power. We got used to the paradigm of western domination over the rest of the world. China, which had to accept this advantage in the 19th century, was perplexed with the imperial impertinence of the European “barbarians”. People’s Republic of China was proclaimed in 1949, and we can consider this date as the symbolic ending of “one hundred years of disgrace and humiliation”. The independent India was also established at that time’, says Dr. Tomasz Okraska, who has been studying Indian-Chinese relations for several years.

We may risk saying that there is one thing that connects China and India – they both aim at rebuilding the political, military, economic and cultural centre of the world in Asia.

‘There is a good reason why one of the official name of China is Zhōngguó (中国), i.e. “Central State”. The Chinese perceive themselves as the civilisation centre of the hierarchical world. There is a lot of evidence to suggest that they are currently also patronising the Indians, although this has not always been the case. Let us remember that it was precisely on the Indian sub-continent that Buddhism was born – it was exported to China by monks via Tibet and then went on to shape the Chinese culture, to a large extent’, explains the scientist from the University of Silesia.

He adds that for political scientists, the measure of importance of particular countries on the international arena is how much attention from USA they receive. Starting from George W. Bush, through Barack Obama, ending with Donald Trump, China and India have been taking an increasingly important place in USA’s foreign policy. In the first case, we can talk about competition, whereas in the second case – about building cooperation. Closer American-Indian relations result from the conflicts of both countries with People’s Republic of China, as well as the weakening position of Russia, which was treated in New Delhi with priority first. Nowadays, Russia is mainly becoming a source of raw materials for China.

What is the position of the European Union in this labyrinth of relations? ‘EU’s significance is mainly based on the technology potential. The Chinese buy shares in European and American companies, for example in Volvo and Mercedes. One of their goals is to transfer technology and adapt new solutions for their production sector. There is a good reason why they are accused of industrial espionage’, adds the research author.

These and other similar activities clearly demonstrate the specific character of Asian political, legal and economic culture. The Chinese and the Indians foster their distinctness. They will definitely not change under the pressure of the West, unless they find that the solutions developed there could be beneficial for them. ‘However, these activities are undertaken with caution, and in both cases their motto could be the words said by Deng Xiaoping, father of the economic success of People’s Republic of China, according to which when you cross the river, you must feel the stones all the time’, says the political scientist.

China and India are superpowers not only in economic and political terms, but also in the military aspect. While being nuclear superpowers, they are also expanding their conventional armed forces, in the recent years putting particular emphasis on the navy. It must be capable of securing the interests of Asian giants that reach the entire globe, and especially the Indian Ocean basin. The trade route that runs across it is currently the most important route in the world in terms of the value of transported goods, used e.g. for transport of energy-producing raw materials to Indian and Chinese coasts. It is no wonder, then, that both countries are preparing for quick response to potential threats, for example by building aircraft carriers, which nowadays are one of the most important attributes of military power.

The Chinese and the Indians are also intensively trying to promote their culture. ‘It seems that India is ahead of China in this race. Bollywood movies and very popular Indian cuisine turn out to be more interesting and accessible than the effects of Chinese efforts. The Chinese, for example, have been trying to break through in international cinematography for years, but the actual results of their actions are far below expectations’, comments the scientist[1].

The cultural element is important. This is due to the fact that economic expansion translates not only into the growing political importance, but also to strengthening the influence of Asian cultural patterns. The current model which functions in a significant part of the world is a result of similar processes, which started at the beginning of the 19th century and contributed to spread of the western standards that are so familiar for us these days.

What makes the broadly understood Asian culture stand out is a certain sense of community opposed to the western cult of individualism. Therefore, a human being both in India and China would be defined first not as an individual being, but through their belonging to the family, circle of friends, smaller social groups (such as Indian castes), society as such, and finally to the Chinese or Indian civilisation.

‘I think that this concept is well demonstrated in the business sphere. The establishment of branches of western companies in China still requires many rituals. The Chinese partner must recognise the business environment and authenticate the operation of a foreign company first. Informal arrangements are more important than the legal regulations, which are often interpreted in a flexible manner. This is part of guanxi (关系) – a complex notion that has no satisfactory equivalent in our language. It characterises a network of personalised contacts, a kind of personal space of influences based on trust and exchange of gifts, which are to help in maintaining connections. In line with the western legal regulations, many of these behaviours might imply corruption, whereas in the Chinese world they are the basis for practising the art of business. It is also worth mentioning that in India, the concept of swadeśi (supporting home production) withheld the process of attracting foreign investments for many years’, says the author of the research.

Another aspect that distinguishes the Asian culture is the pragmatic approach that can be seen in each aspect of life, beginning with support for the political system and ending with the religion.

‘Democracy does not have to be valued in India in its axiological aspect, but it simply allows to find a safe outlet for the tensions in the country which is so varied in terms of religions, social classes and ethnicities. On the other hand, the authoritarianism of the Communist Party in China is generally accepted, as long as its rule ensures ongoing economic development and supports the process of improving the quality of life for the citizens’, explains the scientist.

It is also worth looking at the religious aspects. A Chinese person may be a Buddhist, Confucian and Taoist at the same time, and get something valuable for themselves out of each of these religions. ‘As mentioned by Prof. Krzysztof Gawlikowski, in China it is not strange to see the simultaneous presence of a Buddhist monk, Protestant pastor and Catholic priest at the funeral of one person. We don’t really know what happens after death, so it’s better to prepare yourself extensively’, he adds.

However, let us not be deceived. The Asian culture, despite the pragmatism and sense of community, is heterogeneous. This is perfectly illustrated by the complex Indian-Chinese relations, which have become the object of research conducted by Dr. Tomasz Okraska. The unresolved border issues and tensions related to competition in almost every field definitely do not help to improve these relations. The tourist traffic between the inhabitants of both countries is disproportionate to their populations, and the Indians, when asked about their Chinese neighbour, often talk directly about the lack of trust and sense of danger.

‘Narendra Modi, Prime Minister of India, said during his visit in China in 2015 that not only the Indians and the Chinese do not know each other well, but they also don’t understand one another. Isn’t this a surprising statement? It turns out that a significant development of economic contacts is not necessarily followed by close relations at the social level’, says the political scientist.

So if the inhabitants of two neighbouring superpowers cannot find a mutual understanding, despite the proximity of their civilisations, will we be able to do it?

Małgorzata Kłoskowicz | Press Section

[1] The Asian impulse could definitely be felt during this year’s Academy Awards’ night, when the Best Picture, Best Director, Best Original Screenplay and Best International Feature Film awards were won by the South Korean authors of „Parasite”, the movie directed by Bong Joon Ho.

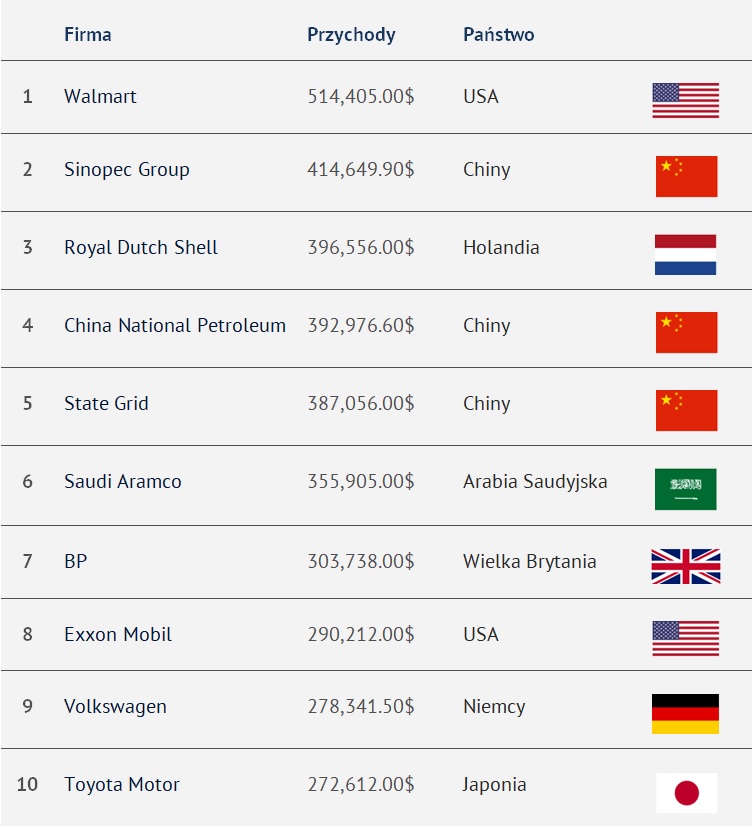

Fortune Global 500 – Top 10

Contact

- Dr. Tomasz Okraska, Faculty of Social Sciences at the University of Silesia: tomasz.okraska@us.edu.pl