Protestant music in Silesia, especially in Cieszyn, is an extremely interesting, though niche topic explored by Zenon Mojżysz, PhD, from the Institute of Art Studies of the University of Silesia in Katowice. He is currently working on a critical edition and publishing of musical works with an interesting story. Found many years later, they can be performed again. This is live music, thanks to which we can experience fellowship with our predecessors from centuries ago, people whom almost no one remembers today.

Olimpia Orządała: You are involved in the elaboration of musical works. What type of songs are these?

Zenon Mojżysz, PhD:

They date back to the first half of the 18th century. It is a part of the repertoire of the Church of Jesus in Cieszyn. In Habsburg times it was the only Evangelical church in Upper Silesia, the so-called church of grace, because it was built “by the grace of the emperor”. After the Altranstadt settlement, the then Emperor Joseph I gave a permission to build six new Lutheran churches in Silesia – five of them were located in Lower Silesia, and one in Upper Silesia, right here, in Cieszyn.

It was a big surprise for me that even before the completion of a brick church, in such difficult, one could say provisional, conditions, musical culture developed so beautifully. Among the preserved works are two arias performed in 1710 during the ceremony of laying the cornerstone for the construction of this church – we have got one piece performed just before the act of laying the stone and the other – after the act. These are very impressive, solemn compositions, in a ceremonial cast, as it was then said: “with timpani and trumpets”. In addition to these two, a dozen or so cantata-type pieces from the first four decades of the functioning of the church have survived to this day. Seven of them, from the earliest period, from 1710–1715, are solo cantatas for one or two vocal voices with an orchestra. We also have several cantatas of a different nature, with a greater participation of the choir, from the period after 1725. The last of them dates back to 1740 – it is a very specific work, serious and dignified, written for the mourning ceremony after the death of Emperor Charles VI.

O.O.: What makes cantatas different from other pieces of music?

Z.M.:

These are vocal and instrumental pieces, then written all over Europe for various occasions, both church and secular. In the Lutheran community, church cantatas were one of the important elements of the religious services. They not only embellished them, but, above all, had theological and didactic functions: they commented on and supplemented the religious content.

The works that I elaborated were cantatas in German. The local people (representatives of the lower estates) spoke mostly the local Slavic dialect, the townspeople and nobility often used both languages (German and Czech/Polish) – also for purely practical reasons, but it was the knowledge of German that was, in a sense, a determinant of aspiration and belonging to of the then “high society”. From the second decade of the 18th century, all official documents of the Church of Jesus were also written in German.

At that time, there were two cantors in Cieszyn. The first was the so-called Czech or Polish cantor responsible for music in the Slavic language. Initially, it was the Czech language, and then more and more Polish works were written. The other one was a German cantor for German-speaking members of the congregation. At least in theory. In practice, however, this division was probably a little bit different, because one of them dealt mainly with the choir and instrumental ensemble, and the other played the organ. Of course, both of them had to work in close cooperation. But this knowledge of languages was important. One of the Cieszyn cantors even wrote a practical Polish-German dictionary.

All in all, the Cieszyn cantatas are a fairly coherent collection of works closely related to the region and the activities of the Lutheran congregation at that time. Of course, this is only a small part, a part of the repertoire of that time – a dozen or so works have survived – there used to be many more of them, probably several hundred in total. Fortunately enough, many of them survived to show a good cross-section of this repertoire. In addition to the fact that the music itself has survived, we also have a whole range of various information about the musicians who were active in Cieszyn at that time.

O.O.: Do we know the authors of the surviving cantatas?

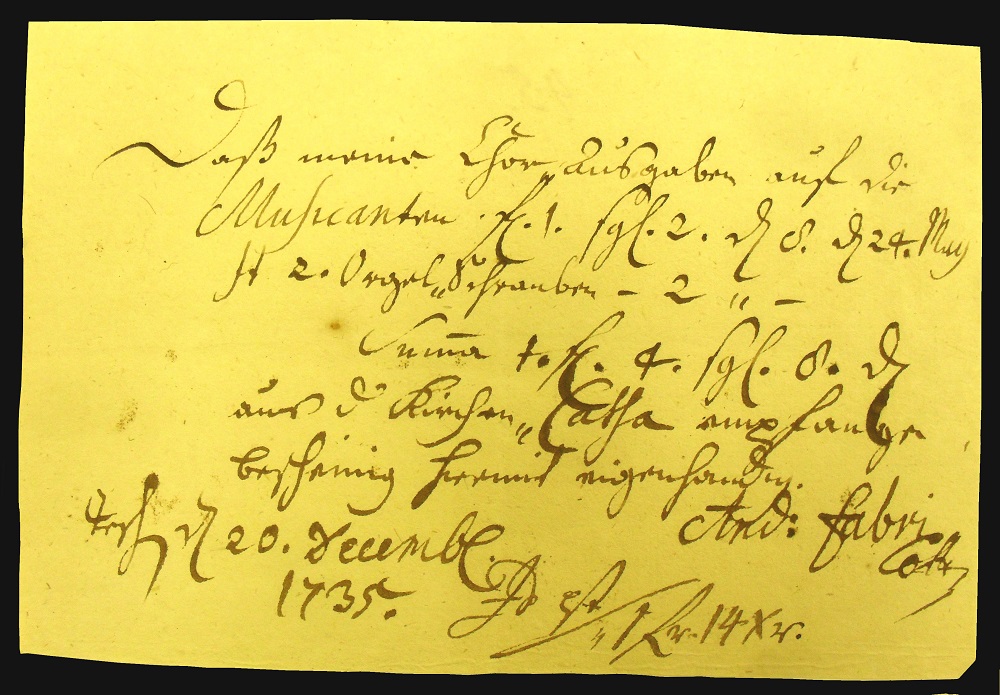

Z.M.: Partly, yes. Only one name appears in the cantatas’ manuscripts – Giovanni Battista Bassani. He was an Italian composer, very famous in the second half of the 17th century, one of the most respected musicians of his time. However, the remaining works are theoretically anonymous. Theoretically, it can be assumed that the author of at least some of the later cantatas was Andreas Fabri, a cantor in the years 1716–1743. When it comes to the earliest cantatas, that is those from 1710–1715, Georg Gürtler was the cantor at that time. But most likely he is not the author of the later ones. The watermarks on the paper, the copyists’ notes and the content of these compositions suggest that they were brought from Wrocław and only adapted to the needs of Cieszyn. In the case of later cantatas, I also can’t say with 100% certainty “this was written by Fabri, because the compositions were not signed”. However, in the case of one work, this mourning cantata from 1740, not only the score and instrumental voices, but also a composer’s sketch – a rough draft with the composer’s ideas, fragments of melodies and texts are preserved in the Cieszyn archives. Since such a draft had survived in Cieszyn, I assume that the whole piece was probably composed on the spot by one of the local musicians – and most likely it was Fabri. It is known, among other things, that he was responsible for the vocal music in the Church of Jesus, took care of the repertoire, ordered copies of sheet music, paper, took care of the equipment of the orchestra and musicians, conducted rehearsals, and so on. It can be deduced directly from the receipts signed by him and preserved in the archive. In one of them, from 1724, Fabri sets out two reams of paper on which cantatas and arias were written. They were composed on the occasion of various celebrations…

Andreas Fabri’s receipt detailing music expenses from 1735 | photo: archive of Zenon Mojżysz, PhD.

O.O.: The pieces were found in the archives of the Church of Jesus and in the Tschammer library in Cieszyn. How were they discovered?

Z.M.:

It all started quite a long time ago, at the end of 2008. At that time, I was a new employee at the then Institute of Music of the University of Silesia in Cieszyn. I finished my PhD thesis and was looking for new research material. One day I came across some leaflets at the institute related to the celebration of the jubilee of the Church of Jesus. I thought that since the church is already 300 years old, maybe some musical “antiquities” have been preserved in the archive. Indeed, I found out that something interesting was found in the collection just shortly before that. It was a fairly thick bundle of dusty sheets wrapped in gray-blue paper. When I saw the name Georg Philipp Telemann on this paper, I was intrigued. After opening the package, I saw old music manuscripts from the beginning of the 18th century. It also turned out that I was probably only the second musicologist who came into possession of them. The first was one the late prof. Karol Hławiczka, who, however, never published anything on this subject, which struck me as strange, because the papers had a piece of paper attached, which indicated that the manuscripts had been reviewed by him. The more I looked at this collection, the more fascinating this discovery became.

Telemann’s name does indeed appear in these manuscripts. In the second part of the collection, among the instrumental pieces, we can find one of his so-called Polish concerts for traverso flute and orchestra. Moreover, it also included works by Heinichen, Stölzl and other less known artists. These pieces were on top of the file, while under them I found hidden vocal and instrumental pieces: cantatas. And it is the cantatas that I have studied in the first place, although in the near future I plan to elaborate on the remaining material as well.

The cantatas themselves, however, are the most important and interesting discovery in this collection. Firstly, it’s very valuable music, and secondly, they’re truly unique. I don’t know any other works of this type from the area of Upper Silesia. These works clearly show that in the first decades of the 18th century in Cieszyn – a town which despite being a princely town still had little importance – a lot happened in the field of music. These are really good, effective compositions. The listener, also the contemporary, will not get bored because they are skillfully constructed and tonally diverse. Interestingly – that speaks well of Cieszyn itself and its former inhabitants – very similar music was played in much larger and more culturally significant centres, such as Wrocław or Gdańsk. When it comes to curiosities, I will tell you that the aforementioned work by Bassani came to Cieszyn from Italy via Gdańsk. On the score there was a note that the Wrocław copyist wrote down the notes from another copy, made on 13 July 1696 in Gdańsk.

I would also like to take this opportunity to warmly thank mr. Marcin Gabrys, who has been taking excellent care of the Cieszyn Tschammer Library and Archives for many years. It was him who gave me access to all these treasures. Without his considerable help, commitment and understanding, my work would have been impossible.

O.O.: What did the process of elaboration look like?

Z.M.:

First, I had to pre-rewrite the notes, taking into account all the characteristic elements that appeared in them, such as instructions regarding the repetition of certain parts in a different scoring or with different text, or notations with different shades of ink, which may mean that some version was created as the original, and later additional fragments were added. In the case of deletions, notes or other corrections, I had to decide which version was correct. It is at this point, the moment when you have to start making such decisions – that’s when the actual work begins.

In critical editions of early music, the most common goal is to present the “final”, verified musical text that may constitute the basis for its contemporary interpretation. The main job of the editor is to recreate the music as it was performed then, but write it down in such a way that it can be performed today. This recreation is made primarily through the philological verification of the original musical text.

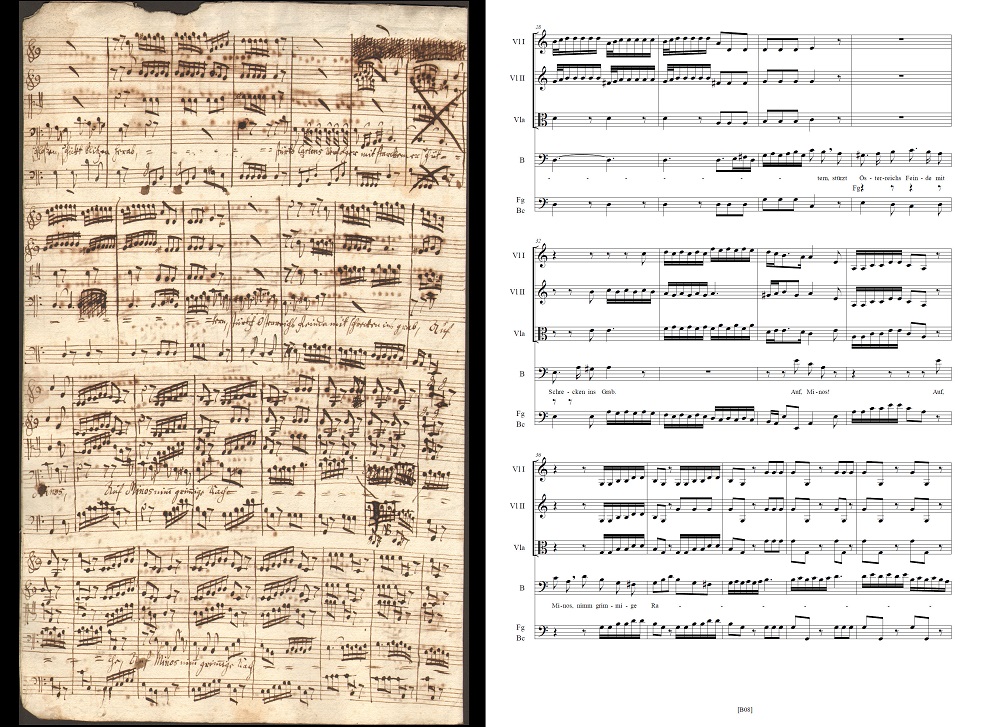

Handwritten original and transcription of a fragment of the aria “Ihr brüllenden Donner” from the repertoire of the Church of Jesus | photo: archive of Zenon Mojżysz, PhD.

If there exist alternative versions of the text, e.g. notation of the score and instrumental voices, partes, you must always compare them, find the differences and decide what is more and what is less important. In this case, in the Cieszyn cantatas, the instrumental voices (at least those that have survived) turned out to be particularly important. After all, it was them that lay on the stands and it was from them that the music was played. That is why they also contain a lot of details that are simply not present in the scores. This doesn’t mean that the scores were flawed, but there was simply no need to write down all the details in them, certainly not those that were relevant only to the performers. However, while working on the “final versions” of individual pieces, contemporary scores, I had to supplement them with all these additional elements from the instrumental voices. This is important because such a combination of all available information about the edited piece can significantly affect its final shape and sound. It may turn out that this is a different music than each of the sources separately suggested.

It is important, however, that from such a contemporary score one can also see what the original handwritten record looked like. Hence the diacritical notation of some elements, for example: a smaller note typeface for added fragments, or the use of a plain or italic font in order to distinguish between the original notes and the notes added by the editor. The entire critical apparatus is also helpful here, i.e. a revision commentary with a detailed description of the sources and, above all, critical remarks which list everything that couldn’t be included in the score itself.

Fortunately, I’m in possession of high resolution scans of all the pieces, which is very helpful in my work. Such scans show not only all the important details of the notation, staves, notes, lyrics in various colors, corrections and blots, but even fragments of paper fibers. I can tell if a given element is, for example, a written dot, or maybe a few hundred years ago a fly passed in this place and left its mark… Of course, there are also some things that must be checked in the manuscripts: entries that are illegible due to dirt and damage, or the layout of the sheets of paper in the scores. The scans also do not show watermarks indicating which paper mill produced the paper used by the copyist. In most cases, however, I don’t have to reach for the originals at all and I work from home.

O.O.: Why did you decide to get involved in the elaboration of the musical works?

Z.M.:

I always try to include the “practical element” in my work. When the prepared score is ready, it becomes available to a wide audience, not only musicologists or interested readers, but also, what is particularly important, for musicians-performers. Cieszyn cantatas were performed several times: in Cieszyn itself, in Katowice, and in Warsaw. Such a performance means live music, intended for the audience, here and now. Then we can try to experience fellowship with our predecessors from centuries ago, people whom almost no one remembers today. You can directly “touch” one of the elements of their life, their times, hear the same sung words, experience similar emotions.

I can write many important and wise texts, articles or books, but many of them will be useful mainly for specialists. Thanks to the editions, in turn, old music, often forgotten, somehow gets a second life and enters the live music repertoire. Its field of influence on the contemporary community is much greater here.

O.O.: Thank you for the interview.

The publication, prepared by Zenon Mojżysz, PhD, is currently being edited and will be published soon.

photo: Pixabay