Krzysztof Zanussi is a legend. We know him not only as a director of Barwy ochronne (Camouflage), Spirala (Spiral) or Iluminacja (The Illumination), but also as a film producer, lecturer and author of books. Awarded with many honorary doctorate titles, he points out not to sign him with an academic title, but with the honorary title. “I gave a lot of interviews in my life and I don’t remember what I said in them. I can repeat myself. I often tell my students the same thing twice, but this is the privilege of the elderly” says the lecturer of Film School in Katowice.

Agnieszka Niewdana: But I think it can be described differently: the privilege of the experience and its value. Let’s move to 1959. You are then 20 years old. Is there anything that you would like to tell your young yourself, but having your current knowledge?

Prof. Krzysztof Zanussi: This is an anachronistic exercise. Because, what would I say having my current knowledge? How would I reflect my social and historical awareness? The fact, that communism will collapse. The world from that perspective looked totally different. This is our general feature – what lies ahead is a mystery – the various choices that are waiting for us. Only when we look back, over time, some things become clear. The fact that I understand my past choices today, doesn’t mean that back then I knew whether I was going the right way. Especially that I changed my studies at that time. I think it is worth mentioning, because today young people are inundated with a huge amount of opportunities and alternatives. I was aware that if there is any path for me to sneak through life, and I find it, I have to hold on to it, because it is terribly easy to waste your life. Fortunately, your generation does not understand it, it doesn’t feel it. For my generation, the mere fact of surviving was already a great success – the fact that we physically survived the war. Well, if so, my life, although in unfavorable circumstances, needed to be planned well. That was my concern. When I said goodbye to physics, I had already known that I wouldn’t become a physicist, I deleted four years of my studies. I thought that I’d wasted my time, but it turned out that I was wrong, although at the time of making that decision I hadn’t seen it yet. I half-heartedly started studying philosophy which I’d chosen out of curiosity, but without any idea what I would do with these studies, what it could be useful for. I was only thinking about how to avoid joining the army, and went to Krakow. There was a renewed Faculty of Philosophy, led by prof. Roman Ingarden. It was the only non-Marxist philosophy department at a state university – a phenomenon in the entire Soviet bloc. These studies seemed to be fascinating – and they actually were. Shortly after that, I was accepted into a film school. I didn’t know if it was a good choice. Now everything seems to make sense, but I know very well that it wasn’t like that back then. Film became my true calling only when they kicked me out of the school three years later.

A.N.: I have the impression that currently the approach to studies has changed quite a lot.

K.Z.: As I remember well, we went to university so that our grandmother would be satisfied with her grandchild’s master’s degree, and the second thing was to think about our obituary, which was simply supposed to look better with a title in front of our surname. Studies are a significant step in development – of course, it is often discovered ex post. I hear it from my students. Years later, they conclude that the studies have given them something, they have been able to use them. We look into our future with a sense of confusion and chaos, we wonder what world we are going to, everything is a mystery.

A.N.: In 2018 your book Uczyń ze swego życia arcydzieło (Make Your Life a Masterpiece) was published. In the book you mentioned that there will come some catastrophe, maybe in the form of a meteorite or a plague. Would you agree with the statement that each generation has to go through its own “war”? A time of trial?

K.Z.: From observation of history it appears that this is exactly what human fate is – it has happened for centuries. Every 20 years, the next generation wanted to flex their muscles. I am aware of that, maybe because I survived the war and communism, and both of these phenomena destroyed my life and took my chance away. On the other hand, I meet with the view that cosiness is what shuold be taken for granted, that I have to be safe and that I should feel comfortable. This is quite bizarre. After all, no one has guaranteed it, no one can promise the continuity of such a state. When we look at the experience of the last century, it turns out that the excess of certainty and security has buried many ideas and plans because they were against human nature. In nature, you have to be vigilant, and one cannot succumb to the illusion that we are owed something. Drama is a natural part of our existence.

A.N.: Do we get used to comfort quickly, and later it is difficult to give up some conveniences?

K.Z.: No one can assure us that everything will be fine and that using all our freedoms and possibilities will last forever. The issue of values is important as well. A great “confusion” was caused by the wonderful and genius professor Maria Janion with her deconstruction of romanticism, and nihilism in general, which reflects in all her works. It spilled over into the entirety of cultural studies. It’s a result of the pursuit of theory that will justify everything and eventually make everything relative, while relativism ends in nihilism. To condemn romanticism is to condemn idealism.

A.N.: Looking for answers to nagging questions such as the meaning of life, work, etc. lies in our nature. We’ve been looking for an answer to the question of the truth for centuries.

K.Z.: Once upon a time, probably Ronald Reagan, who was not an intellectual but had many good quotes as an actor, said: “The truth is generally simple. But it’s hard”.

A.N.: The search for truth is a challenge. It reminds me of a constant state of vigilance. Such a state is perfectly reflected in your films. The characters’ values are challenged all the time.

K.Z.: And, of course, many are irritated and angry because the superficial calm is disturbed. When someone is moving on thin ice, it is irritating to notice that the nature of the ice is to crack. I understand such public reactions. These questions also touch our commitment to consumerism, because people who wonder don’t spend all their free time choosing a branded handbag, but we are constantly encouraged to do so. When I turn on the radio in the morning, I still have to listen to advertising blocks. One of the ads urges you to ”Buy more”, but I would like to hear the message ”Buy less, try to limit the damage that you make to the planet.” I am wondering what’s the purpose of consuming so much – both literally and figuratively.

A.N.: One should be aware of this, and not be afraid of going beyond certain habits that seem beneficial.

K.Z.: This has to be confronted. Especially when we focus on the far-reaching costs and effects of such messages. I think that some kind of work will be over in a while. We will stop working for money, and start working for other reasons. Work is essencial, as is physical exercise. Sitting and lying down would kill us because that’s the way our organisms are built.

A.N.: Studies also prepare us to work and think about the world in a certain way. An excerpt from your book drew my atention – the one concerning students. At the first meeting you don’t ask them what they would like to do professionally, but what they are good at, what they can do. It changes the perspective.

K.Z.: In general, the question “What do you want to do?” is a reflection of wildly unbridled voluntarism. Why? Because nobody actually cares about what “I want” . There’s no need to bother with it, there will always be a more important question, “What can I do?” and that actually means “What can I really be useful for?” and “Where is the place for me?” – not what place I dream of. Of course, we can fight for this place, but it must be done without the approach that we deserve it by definition. Nobody says that world has prepared a place for us.

A.N.: Political correctness, as well as the prevailing trends in self-improvement, would disagree and state that everyone has equal opportunities and can do anything.

K.Z.: Political correctness is an act of great cowardice. It is morally reprehensible because it is based on a lie, and it is a bit like living on credit, as the conflict is postponed until tomorrow. If we don’t want to accept any scale of values, we have to be aware that the consequences will come anyway. Similarly, the issue of diversity which cannot be judged, although we are aware that, for example, it is possible to clearly define the degree of development of certain cultures.

A.N.: A few years ago you were a guest at a meeting at the current Faculty of Humanities. As an answer to your statement on cultures a comment was made – that cultures cannot be valued, after all each of them is important, different…

K.Z.: This is how it is taught in cultural studies.

A.N.: Categorical judgments are not what is expected now. Don’t you care about nice atmosphere?

K.Z.: This is a pudding in which our life has immersed itself, and it has a disastrous impact. Relativism destroys values and thus, deprives us of an opportunity to grow. We can stop growing as a culture; however, just a passive existence is not in accordance with the laws of physics. Either we go forward or we go backward.

A.N.: Although living by any rules seems to be a challenge. You show this in your films as well – that this choice isn’t easy.

K.Z.: Living against the current leads to the spring. This can be treated as worn out rhetoric, but there is a statement behind it – that people must have the courage to look at their own condition. Otherwise they degrade. They become more like animals that have their own intuition, instinct, but use intellect to a limited extent. Human has more possibilities and it would be a pity not to take advantage of them.

A.N.: We have examples of writers who are tormented by the aforementioned “view of their own condition” throughout their lives. Professor Jan Józef Szczepański comes to my mind.

K.Z.: There is no reason to be surprised. When someone took part in the war, he fired shots, then if he has human sensitivity, he has to think about the value of life and death. What was important for him was that he did not run away like many, he did not forget and did not distort the history and experiences. On the other side we have Rev. Jan Zieja, who said to the Warsaw insurgents, “Do not kill anyone.” When he was later asked if he had been listened to, he replied that he had not. Of course, you can surround yourself with a group of yes-men, which can be a temporary pleasure. In history, we have examples of rulers who had courts created from this type of people, and their fates ended in a collapse. The role of a human towards another human is also criticism. If someone is pushing close to the edge, they should be warned, and if it is not done out of courtesy, then one has to reckon with the fact that they will be lost, similar to the aforementioned rulers.

A.N.: The time of the pandemic gave us a lot of opportunities for reflection, and it reevaluated many things. It is also a critical moment in teaching. You still lecture, incl. at Krzysztof Kieślowski Film School.

K.Z.: I am happy to see my students, even only on the screen. It is a difficult time for me as well. Normally, I used to go abroad or to another Polish city once a week. I miss the students, I would love to meet them and talk to them already. A lecture through a glass is not the best form of communication, it cools down relationships. The students are tired as well, and I feel this. However, it is still a common belief that the university has to give you something. My opinion is slightly different. The university, indeed, offers a lot, but what students will take from it, what kind of education they will gain – it is up to them. Merely graduating from a university of any kind doesn’t guarantee anything. On the other hand, I am particularly appreciative of the University of Silesia in Katowice. I’ve been associated with it since the late 1970s. It used to be a pain when train journeys were mercilessly long, but these times are now over.

A.N.: I hope that you have more memories with the University of Silesia than just delayed trains.

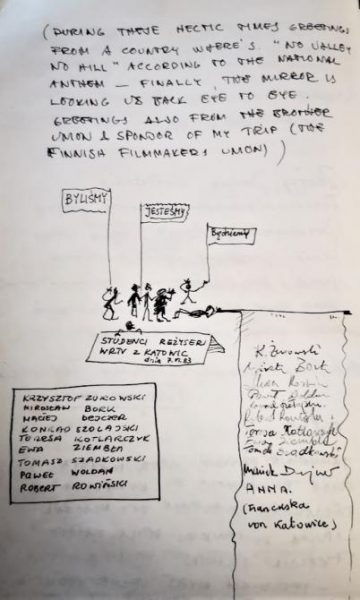

K.Z.: I was touched by this place when I was invited to work here. Back then, I had a lot of uncertainty in myself, because it was the moment I was thrown out of the Film School in Łódź. The then rector put forward ideological arguments against me and Krzysztof Kieślowski. He said that we have a bad influence on the youth because we are oriented towards the West and co-productions, which was actually true. The University of Silesia didn’t have a good opinion – we all remember when it was established. However, this opinion didn’t correspond to reality. Szczepański, the head of television and the propagandist of Gierek, ensured us autonomy. He gave us an umbrella and let us teach. Although not explicitly said, that was the truth. Nobody controlled us. The students were extremely eager to cooperate, it seems to me that even more than the students from Łódź, where I often encountered a pretentious artsy attitude. Silesia imposes a certain kind of humility towards life and art as well. I still remember my first students: Lang, Krzystek, Bork… We were full of dilemmas as to whether to continue our activities under the martial law. I still have an entry in the guest book, which my students also signed, leaving a funny drawing with the slogan: We were, we are, we will be. Hence, we continued to work in this difficult time. Kazimierz Kutz and Wojciech Kilar were my guides through Silesia. They could describe this place in such a way that I immediately liked it.

A.N.: Thank you very much for the interview.

The article „The role of a human towards another human is also criticism” was published in the June issue of Gazeta Uniwersytecka UŚ 9 (289).

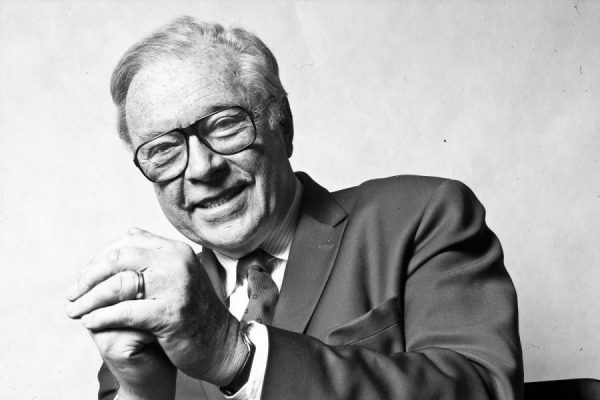

Prof. Krzysztof Zanussi – lecturer at Krzysztof Kieślowski Film School of University of Silesia in Katowice | photo by Mikołaj Rutkowski